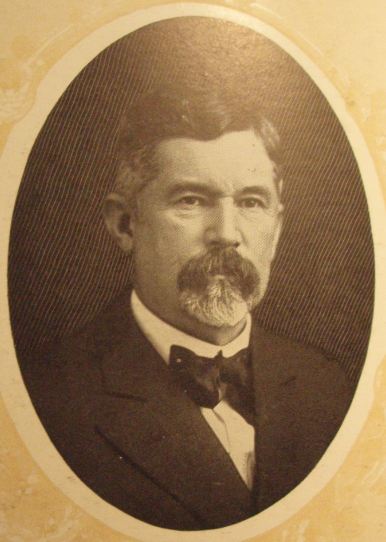

Vail & Gates, 1888-1909

1888 Tax Assessment

Two tax assessment forms were filed in 1888. One for the Empire Land & Cattle Company which declared over 3,400 acres of land, 8,360 cattle, 190 horses, 304 bulls, and 4 mules. The second one was for Vail & Vosburg’s Pantano Ranch that paid taxes on 2,280 acres of land, 2,300 cattle, 20 horses, 85 bulls, and 2 mules.

Overgrazing Problems - 1888

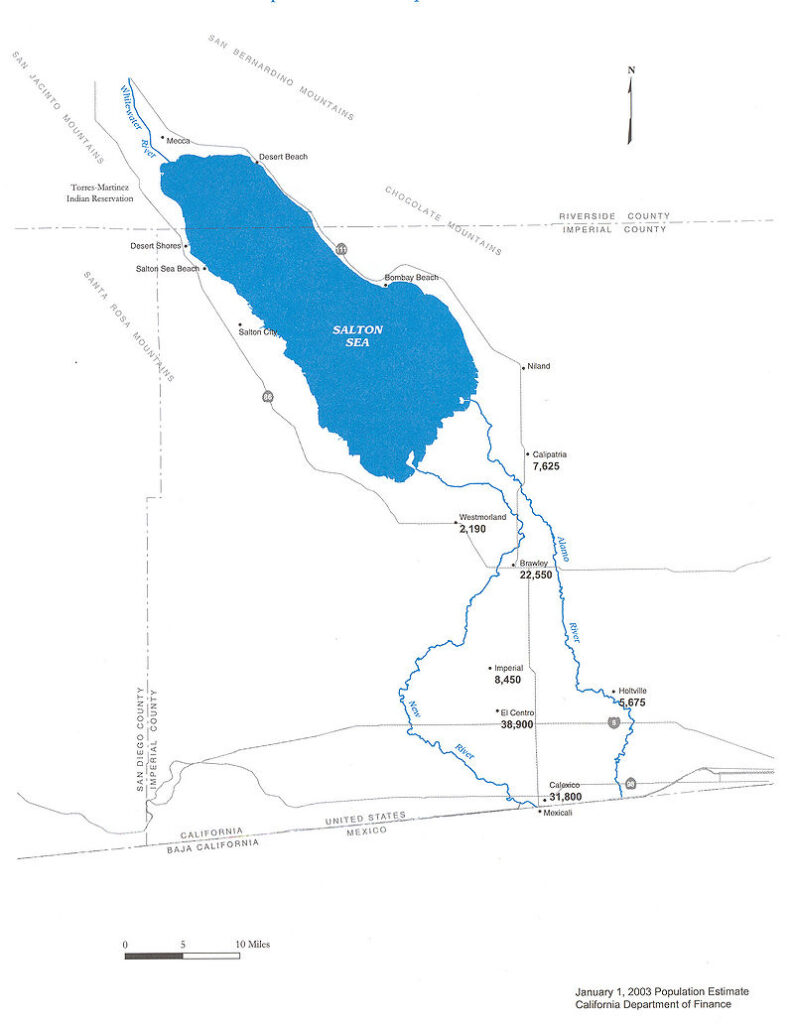

In the late 1880s overgrazing in Arizona was beginning to be a serious concern. In October Walter Vail went to Tempe, AZ and arranged to lease “500 acreage of alfalfa pasturage” and purchased 200 tons of hay to fatten his cattle. [Tucson Citizen, 10/6/1888]. He also began to look for property in California. In 1888 he and a new partner, Carroll W. Gates, leased the 26,700-acre Warner Ranch in San Diego County.

View a summary of the forces at work in Arizona ranching here.

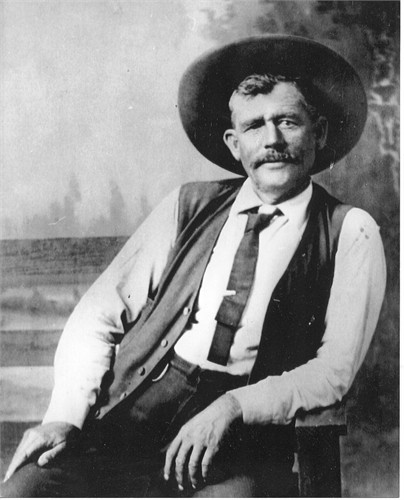

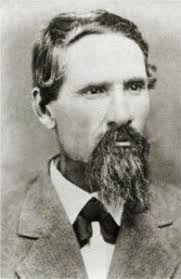

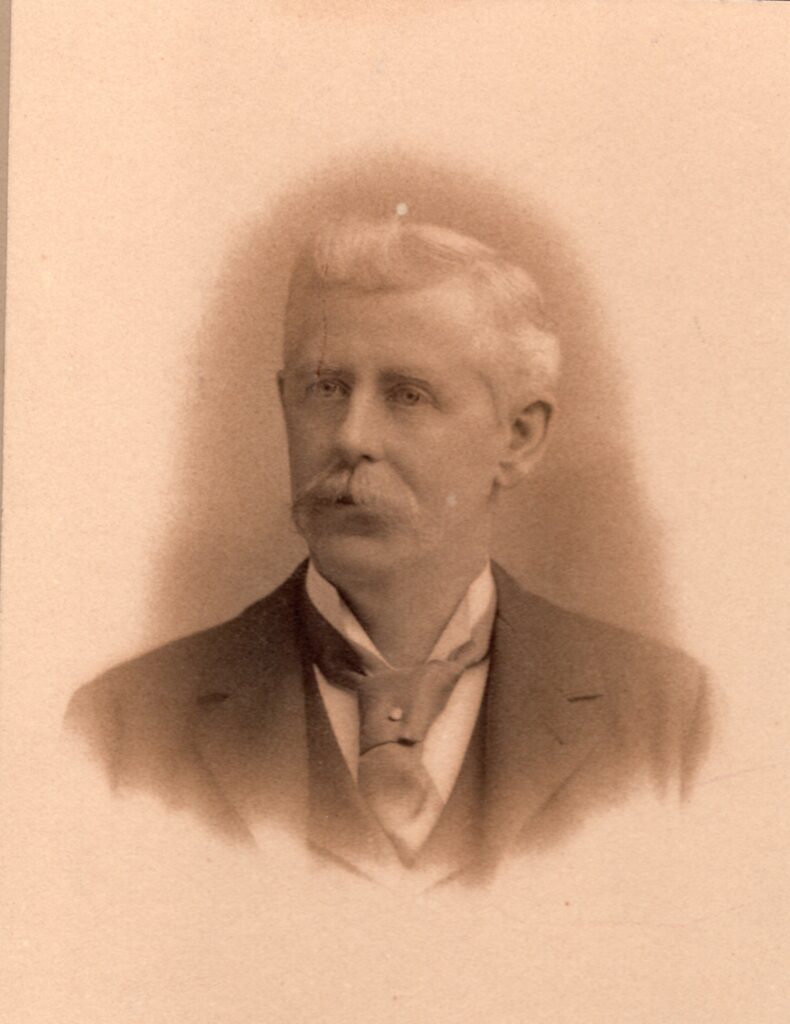

Carroll W. Gates (1860-1920)

Carroll Gates was born in New York in 1860 and moved at an early age with his family to California. Educated in the San Jose area he first worked for David Jack’s Pacific Grove Resort at Monterey from 1880 to 1887. In 1887 he moved to Los Angeles to deal in real estate with A. E. Pomeroy. He knew nothing about ranching, but his strong business and investment background proved extremely helpful to Walter Vail.

William Banning Vail - April 1889

The fourth of Walter and Margaret’s children, William Banning Vail, was born in Los Angeles on April 13, 1889. He used his middle name, Banning, and was named after Walter Vail’s good friend, William Banning, whose family owned Catalina Island from 1892-1919.

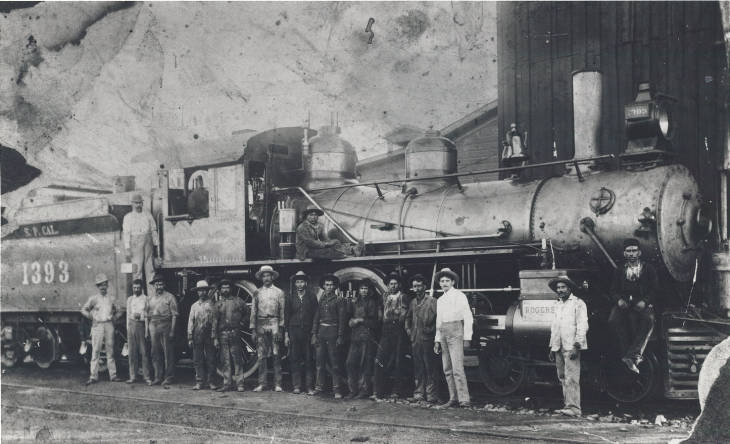

Southern Pacific Railroad Announces Rate Increase - 1889

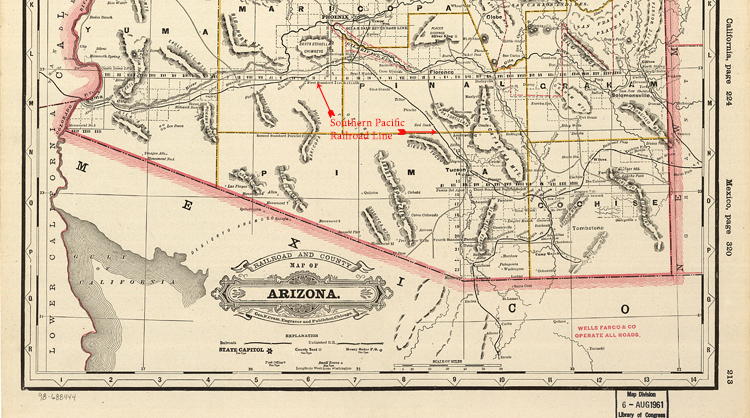

As overstocking increased in the late l880s, Vail and Gates had begun shipping more yearlings and two-year-olds to Warner’s Ranch near San Diego. In fall of 1889, just before the larger ranchers commenced their annual shipments of stock to winter pastures outside Arizona, the Southern Pacific raised its rates to various points in California. Company officials in San Francisco believed Arizona cattle growers could afford a twenty-five percent increase and would have no alternative but to accept it.

Defying the SPR Rate Hike - January 1890

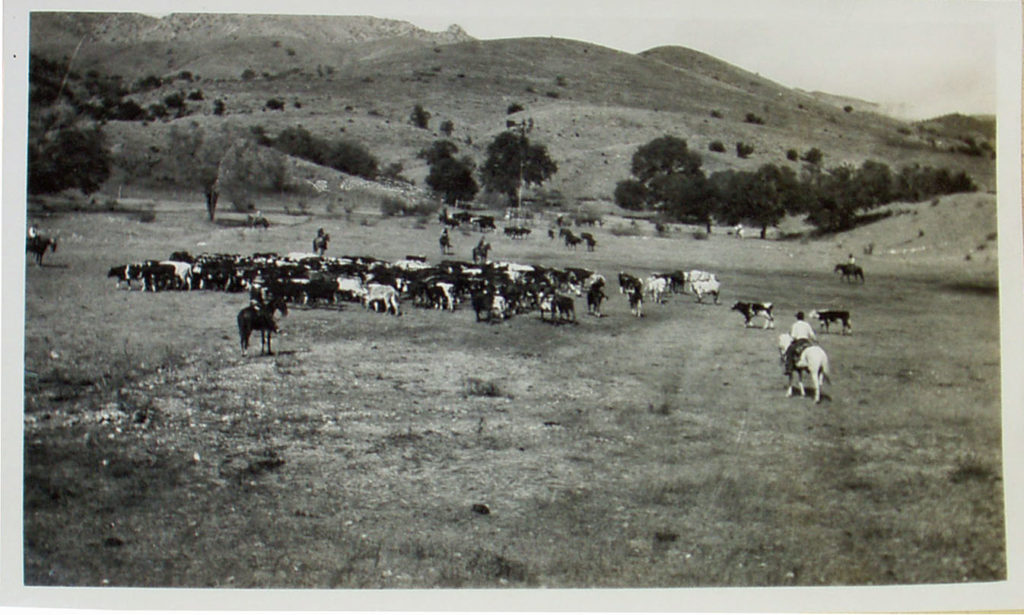

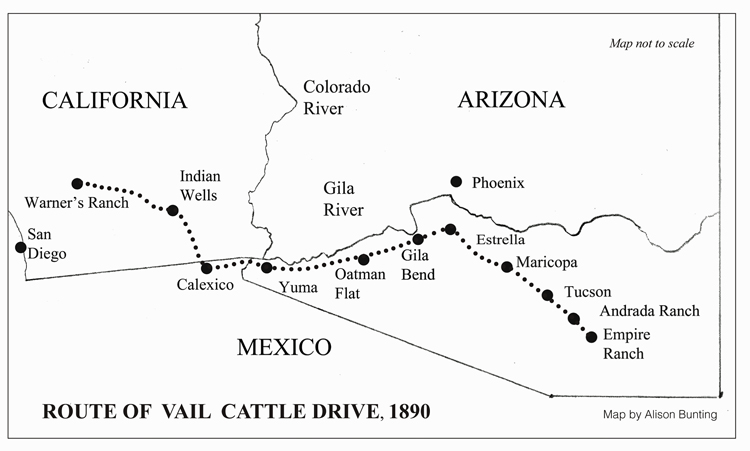

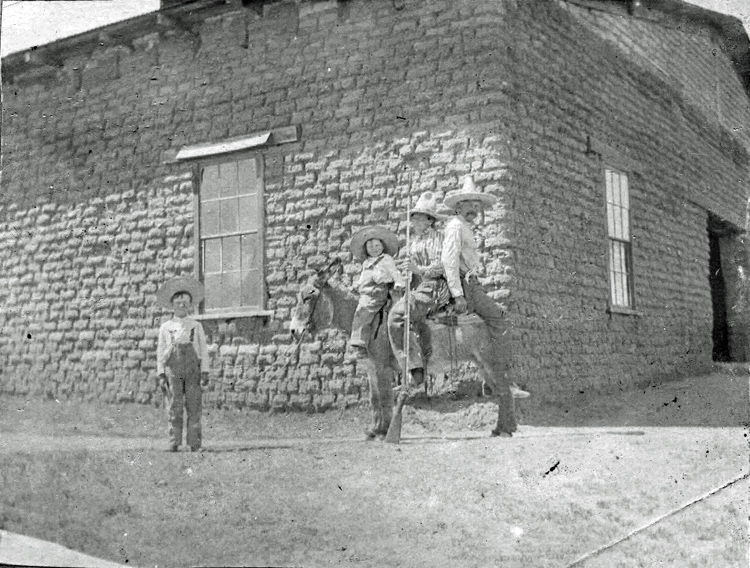

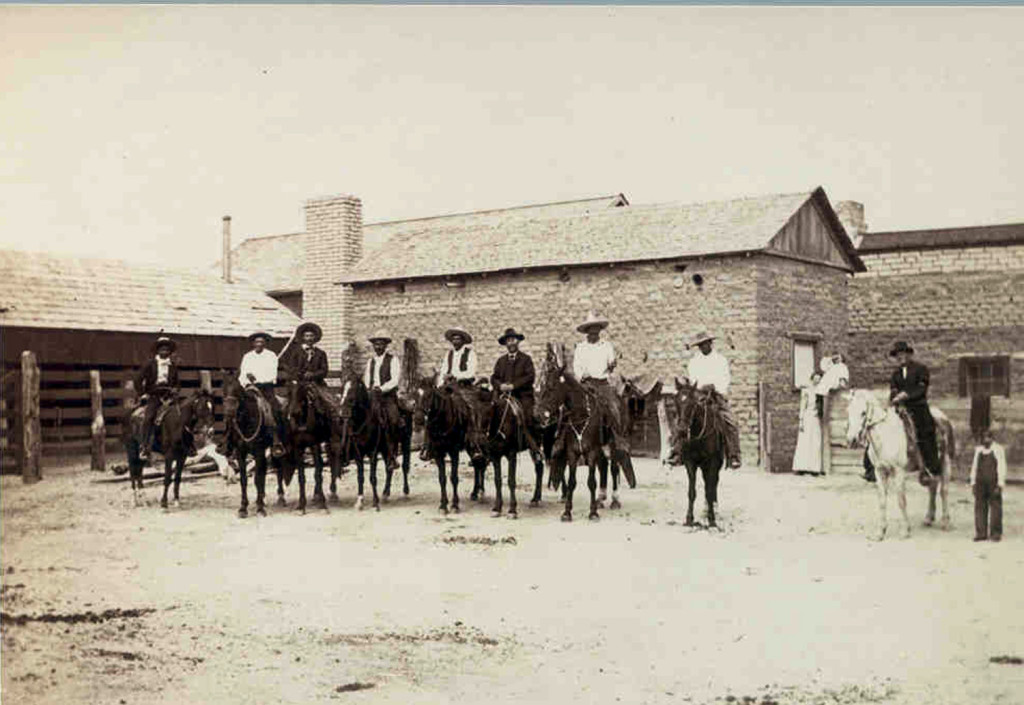

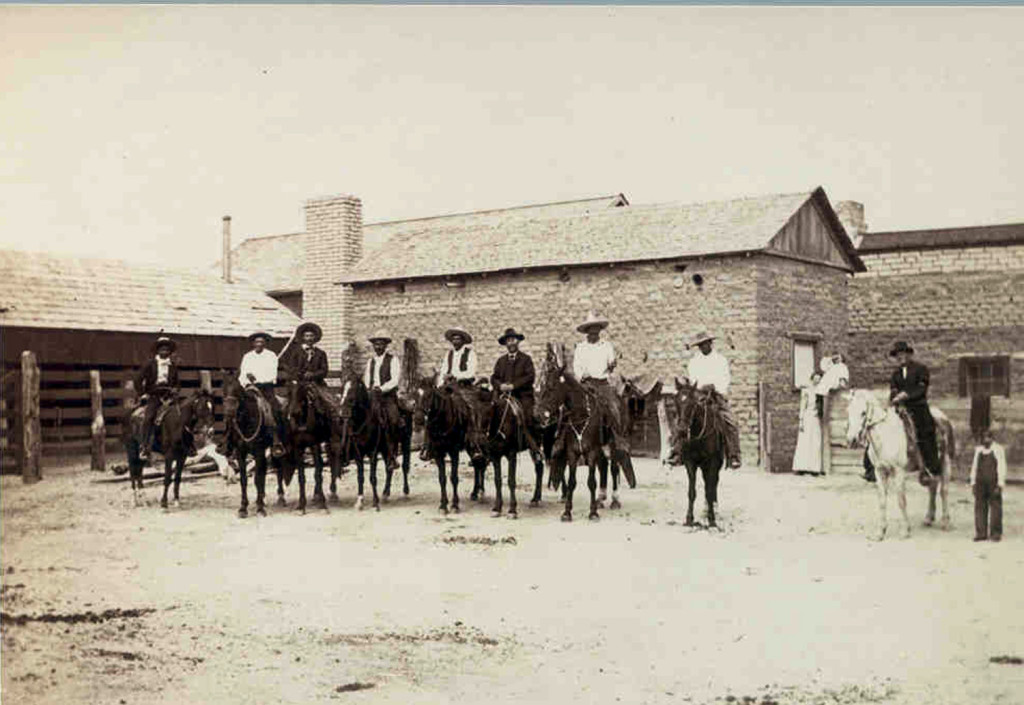

Rather than accept the Southern Pacific Railroad price increase Tom Turner, foreman of the Empire Ranch, and Edward “Ned” Vail volunteered to drive 900 steers overland to the Warner Ranch.

The drive began on January 29, 1890 and ended 2 months and ten days later. In addition to Edward Vail and Tom Turner the men who participated in the drive included “six Mexican cowboys from the ranch and a Chinese cook.”

Defying the SPR Rate Hike - January 1890

Rather than accept the Southern Pacific Railroad price increase Tom Turner, foreman of the Empire Ranch, and Edward “Ned” Vail volunteered to drive 900 steers overland to the Warner Ranch.

The drive began on January 29, 1890 and ended 2 months and ten days later. In addition to Edward Vail and Tom Turner the men who participated in the drive included “six Mexican cowboys from the ranch and a Chinese cook.”

Diary of a Desert Trail - 1890

In 1922 Edward Vail shared the colorful story of the cattle drive, which he recorded in his diary, through a series of articles in the Arizona Daily Star. The Empire Ranch Foundation re-published the articles in 2016 as the Diary of a Desert Trail. The posts that follow were written by Edward Vail.

Diary of a Desert Trail can be purchased from Amazon—we hope that the excerpts will prompt you to read the full story.

Empire Ranch to South of Tucson - 1/29/1890

“We left the ranch the 29th of January and after watering and camping at Andrada’s that night, we drove on and found a dry camp on the desert about 15 miles southeast of Tucson. Our cattle were still steers: there were over 900 in the bunch and as most of the big ones had been gathered in the mountains, they were very wild and none of them had been handled on the trail before.

The part of the desert where we made camp was covered with chollas, a cactus that has more thorns per square inch than anything that grows in Arizona. Cowboys say that if you ride close to a cholla, it will reach out and grab you or your horse, and as the thorns are barbed it is very difficult to get them out of your flesh. They also leave a very painful wound.”

Empire Ranch to South of Tucson - 1/29/1890

We left the ranch the 29th of January and after watering and camping at Andrada’s that night, we drove on and found a dry camp on the desert about 15 miles southeast of Tucson. Our cattle were still steers: there were over 900 in the bunch and as most of the big ones had been gathered in the mountains, they were very wild and none of them had been handled on the trail before.

The part of the desert where we made camp was covered with chollas, a cactus that has more thorns per square inch than anything that grows in Arizona. Cowboys say that if you ride close to a cholla, it will reach out and grab you or your horse, and as the thorns are barbed it is very difficult to get them out of your flesh. They also leave a very painful wound.

On to Tucson - February 1890

With breakfast before daylight our cattle were headed toward Tucson and “yours truly” rode on ahead to buy a new chuck-wagon and have it loaded with provisions and ready for the road. I had two 40-gallon water barrels rigged up, one on each side. John, the cook, came into town after breakfast and exchanged his old chuck-wagon for the new one.

Our camp that night was to be on the Rillito Creek, just below Fort Lowell, about eight miles northeast of Tucson. We drove the cattle east of Tucson, past the present site of the University of Arizona and over what is the “north side” now, the best residence section of the city. At that time, the foundation of the University’s first building was just being laid and it was about a mile from there to the nearest house in town. The surrounding country was covered in greasewood (creosote bush).

Tucson to Maricopa - February 1890

We followed the general directions of the S. P railroad. The watering places were from 15 to 20 miles apart until we reached Maricopa, but several times we had to water in corrals. That night we camped between Casa Grande and Maricopa. Turner and I concluded we would try to get a good night’s sleep for once. We had been sleeping with all our clothes on and our horses ready saddled near us every night since we left the ranch, but as the cattle had been more quiet than usual for several nights past, we concluded to take off our outside clothes and get a more refreshing sleep. Sometime near midnight I awoke and was surprised to find we were in the middle of the herd and a lot of steers were lying down all around us. I awoke Tom quietly and asked him what he thought of our location. He answered, “The only thing to do is keep quiet. The boys know we are here and will work the cattle away from us as soon as they can do so safely. If the brutes don’t get scared we will be all right.”

The boys moved the cattle away from us a short distance, and not long after we had the worst stampede of the whole trip. Tom and I jumped on our horses without stopping to dress and we finally got most of the steers together, but as it was still very dark we could not tell whether we had them all or not. As soon as we had the cattle quieted, we made a fire and put on our clothes. We were nearly frozen.

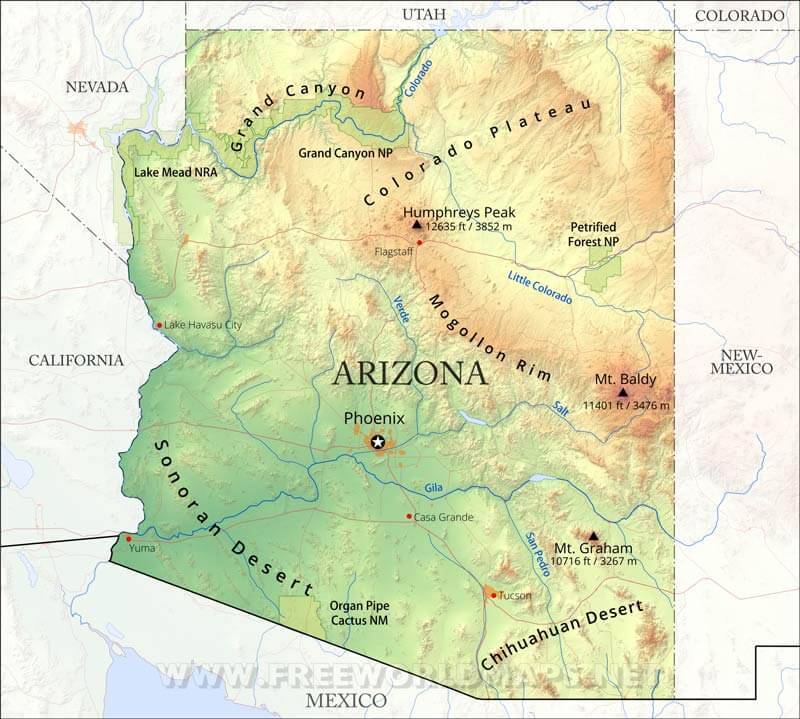

Which route to take from Maricopa? February 1890

The next day we reached Maricopa. At this point there was a choice of two routes; one went north and then followed the Gila River, which makes a big bend to the north here. This route would give us plenty of water but would be much the longest. The other way was to follow the old stage road along the S. P. railroad to a place near Gila Station and then drop down on the river. This meant a drive of 50 miles without water but was about half as far as the other and gave us a chance to find a little more grass for our cattle, as well as our horses which needed it badly. As we expected, our trail ran through a very poor country to find grass or other feed for either horses or cattle. We had two horses to each man and a few extra.

Maricopa to Estrella - February 1890

In the afternoon we hit the trail for Gila Bend, and driving out slowly about ten miles on the old stage road riding the north side of the railroad, we made a late camp for the night. The next afternoon we reached Estrella, which is at the head of a valley which would be rather pretty if it were not so dry. There are desert mountains on each side and south of the little station a mountain higher than the rest forms a rincon. Tom concluded we would turn the cattle loose that night by grazing them in the direction of that mountain and then guarding them only on the lower side, thus giving them a chance to lie down whenever they liked, or to eat any grass or weeds they could find. I remember it was a beautiful night and not very cold. In the moonlight, I could see the cattle scattered around on the hills and could hear the boys singing their Spanish songs as they rode back and forth on guard. I am not sure whether cattle are fond of music or not, but I think where they are held on a bed ground at night, they seem better contented and are less excitable when the men on guard sing or whistle. This custom is so common on the trail that I have often heard one cowpuncher ask another how they held their cattle on a roundup. The other would reply, “Oh, we had to sing to them!”

Estrella to Gila Bend - February 1890

We expected to reach Gila Bend on the river the next evening and started the cattle early in the morning toward the Gila Valley. We had reached a point which was clear of the hills on a big flat that gradually sloped toward the river; suddenly, the big steers in the lead threw up their heads and commenced to sniff the breeze, which happened to be blowing from the river, while a weird sound like a sigh or moan seemed to come from the entire herd. I had been driving cattle for many years, then, but had never heard them make that noise before. They were very thirsty and had suddenly smelled water! They had been dragging along as if it was hard work even to walk, but in a minute they were on the dead run. Every man but one was in front, beating the head cattle over the heads with coats and slickers trying to check them, as we feared they would run themselves to death before the water was reached. Close to the river we turned them loose, or rather they made us get out of their way.

The lead steers plunged into the Gila River like fish hawks, drinking as they swam and crossing to the other side. The drags (or slow cattle) must have been at least three miles behind us when the first steers reached the river and, after watering our horses, which we did carefully, some of the cowboys went back to help the man we had left behind to follow them in.

Gila Bend to Oatman Flat - February 1890

We grazed our cattle and horses at Gila Bend for several days and gave them a chance to rest. Turner or I generally did some scouting ahead to find a good watering place for our cattle and the next day’s camp. We found a trail along the south side of the river, about 30 feet above it, with a steep mountain on the other side and only wide enough for a man on horseback to pass. We followed it for about a mile and it brought us out on the Oatman Flat., a nice piece of land named for the Oatman family, the members of which were killed there by the Apaches in 1850. The way of reaching this place was over a very rocky mountain road and much longer. We decide to drive the cattle over the trail by the river. The cattle were started in that direction with a rider leading them as usual. As soon as we had a few lead steers on the narrow trail the others followed like sheep and all reached Oatman safely. So many cattle walking single file was an unusual sight. The wagon had to go by the longer road. At the Oatman Flat we met the Jourdan family, with whom we were acquainted. Turner and I spent the evening very pleasantly at their house. The Jourdans were doing some farming and also had cattle. Gila Bend is about half way between Tucson to Yuma, and from what I saw of the Gila Valley I did not think much of it as a cattle country. We had some trouble with quicksand when watering cattle in the river. If a steer got stuck in the sand the only way to get him out was to wade in and pull out one leg at a time and then tramp the sand around that leg (this gets the water out of the sand which holds it in suspension). When all the legs were free we would turn the animal on its side and haul it to the bank with our reatas.

A Hot Bath at Agua Caliente - February 1890

While we were at Gila Bend I went with the cook and his wagon to Gila station and bought barley for our horses and provisions. Before we reached Agua Caliente (Hot springs) near Sentinel I rode on ahead as we heard there was a store at the springs and laid in another supply there. The hot springs are on the north side of the river, and as there was considerable water in the river there a man in a boat rowed me over. I took advantage of the opportunity and enjoyed a good bath in the warm water, which is truly wonderful. I doubt there is any better in the country. At that time the accommodations were very poor there for persons visiting the springs, especially for sick people.

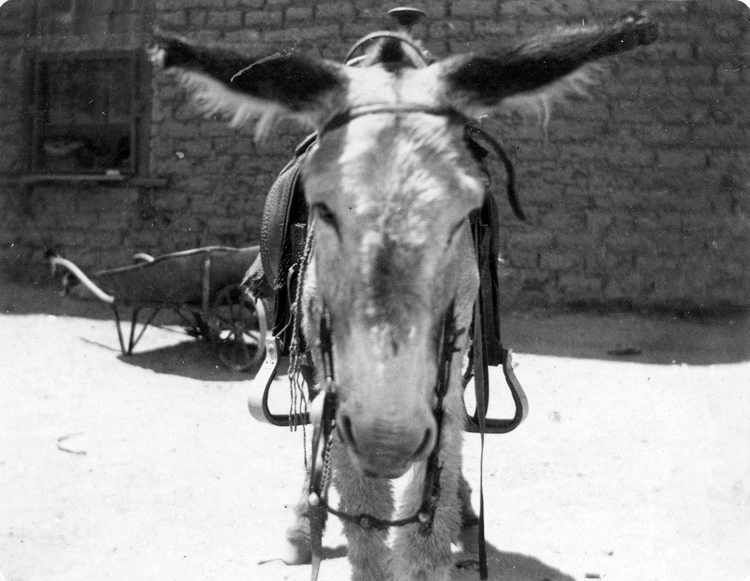

Replacement Horses and Mules - February 1890

About 30 miles from Yuma, Jim Knight and one of his cowboys met us – Knight was the foreman of the Warner Ranch and a cousin of Tom Turner’s. He brought us saddle mules and horses and they were all fat. These were to take the place of some of the horses we had ridden so far.

The mules Jim brought were young and unbroken and as stubborn as only a mule can be. It was hard to turn one around on a 10 acre lot. Two of our boys refused to ride them. We told them if they would go as far as Yuma we would pay for their fare back to Pantano, as that was the agreement we made with our men before leaving the ranch, but I think they were homesick and I could not blame them much. We paid them off and they took the next train for Tucson at the nearest station to our camp.

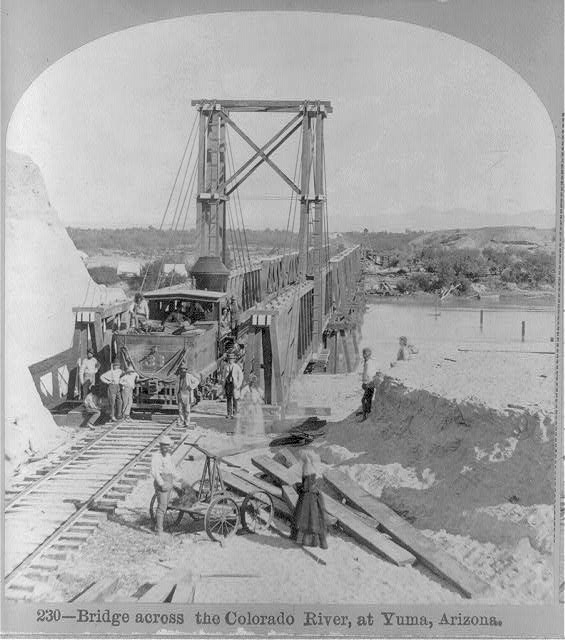

Yuma At Last - February 1890

In a few days more we reached Yuma and camped on the Colorado River, about three miles southwest of the town. The river was rather high owing to an unusual amount of water flowing into it from the Gila which joins it on the north side of the town. The next day we let all of our cowboys go to town to buy some clothing, which some of them needed badly and we gave them free rein to enjoy themselves as they pleased. Of course they did not go all at one time as some had to stay and herd the cattle. Among the last of our men to get back to camp that night was Severo Miranda (Chappo). Pa Chappa as he is called now, commenced working at the Empire Ranch about 1880 and is still on the payroll [1922].

Preparing to Cross the Colorado River - February 1890

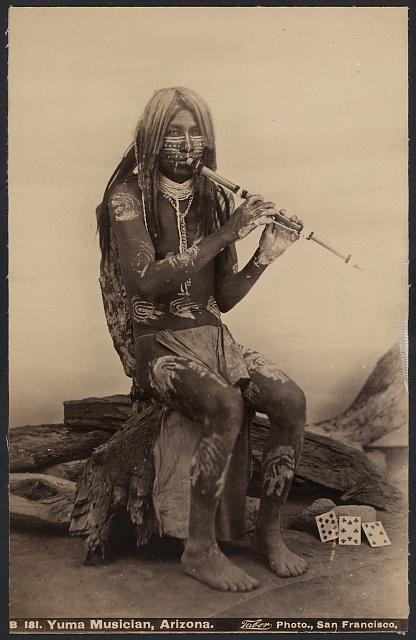

Turner and I got a boat with an Indian to row it, and spent the day looking for the best place to swim the cattle. We rode two or three miles up and down the Colorado River and prodded the banks with poles to see how deep the quicksand was. We found it very bad, especially on the west bank where the cattle would land. Finally we found an island near the west bank of the river where the landing was better. The water was not very deep from the island, with a good landing on the other side. We then returned to the Arizona side of the river and found it was impossible to drive the cattle into the river, there as the bank formed a 10-foot perpendicular wall above the water. We hired a lot of Yuma Indians with picks and shovels. They graded a road to the water. This work occupied a day or two. We were then ready to attempt taking the cattle across.

Crossing the Colorado, Day 1 - February 1890

The herd had not been watered since the day before in order to make them thirsty. The current was very strong and the river very deep. We found it would be impossible for men on horseback to do anything in guiding the cattle across, so we hired the Indians and three or four boats. We placed them so as to keep the cattle from drifting down stream. The idea was not to let them turn back for land so far down as to miss the island. We got the cattle strung out and traveling as they had on the trail with the big steers in the lead and men on each side to keep them in position to go down the grade which we had made to reach the river. Most of the large cattle reached the island all right. Then our troubles began!

Two or three hundred of the smaller steers got frightened as the current was too swift for them and they swam back to the Arizona side. About this time the sheriff from Yuma showed up and said he had orders from the district attorney to hold our cattle until we paid taxes on them in Yuma County. I told him I thought the district attorney was mistaken but we were too busy to find out just then. Cattle were scattered all along the river on the Arizona side and as they could not climb the banks and get out, many of them were in the water just hanging to the bank with their feet. We hired all the Indians we could get and with the help of our own men we pulled all excepting two or three of the cattle up that steep bank. It was then about 10 o’clock at night.

Crossing the Colorado, Day 2 - February 1890

In the meantime here is the way we were situated. Our chuck wagon, cook and blankets were across the river; our 600 cattle were loose on the island in the river where we could not herd them; nearly 300 steers were loose in the thickest I have ever seen and on the Arizona side: and we were in the hands of the sheriff of Yuma county. The next morning Mr. C. W. Gates arrived on the train from Los Angeles. He went down with us to the scene of yesterday’s operations. The first thing we did was to pull out the two steers we left clinging to the river bank. Then we told Mr. Gates that if he would take what men we could spare and start to gather the cattle we had turned loose in the brush that Tom and I would go over in a boat to the island and swim the cattle over to the California side of the river. Throwing our saddles into the boat leading the horses, swimming behind, we soon reached the island. The cattle seemed to be all right. We did not have any trouble in getting them over as we found the big steers could wade across, but most of the younger ones had to swim a short distance. When we got them all across, we looked up the best place we could hold them and made camp.

Mr. Gates and John the Cook - February 1890

When we got back to where we had left Mr. Gates we found him and Chappo on a boat along the river bank. Mr. Gates said, “Tom, you can never gather those cattle in that brush,” and I admit it did not look possible. At that time Mr. Gates had only been a short time in the cattle business and never worked them on a range. So Tom and I told Gates if he would go to Tucson and see his attorney about the tax matter we would gather the lost cattle if possible.

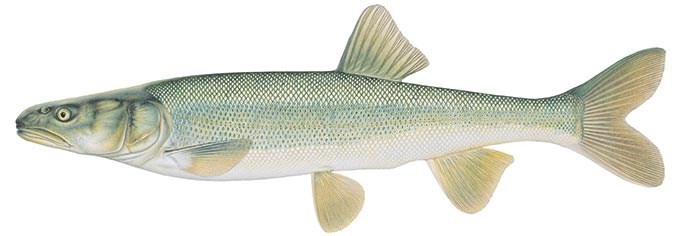

I forgot to say how our Chinese cook left for Pantano on the train soon after we arrived in Yuma. He said if he crossed the river he would never come back again. The day before he left he bought a large Colorado salmon alive from a Yuma Indian who had just caught it. John took the fish, which was over two foot long, up to Mr. Gandolfo’s store and got permission to put it in a large galvanized water tank in the back yard. John said: “I am going to take that fish back to the Empire Ranch for Mrs. Vail.”

Gathering the Cattle in the Brush - February 1890

At first we did not make much progress in gathering those steers. The brush was so thick we could not get through it on horseback. It was screw-bean, which does not grow high but the limbs are long and dropping on the ground and lying there between them arrow weed was as thick as hair on a dog and higher than a man’s head. We found that we could run some of the steers out of the brush afoot by starting near the river and scaring them up to the open mesa as the brush only extends back a short distance from the river. After a few days the cattle commenced coming out themselves and we soon had quite a bunch together.

After four or five days we had gathered most of the cattle on the Yuma side. Then I ordered cars and shipped them across the bridge there. We made a chute of an old wagon box and railroad ties and unloaded them. It would no doubt have been cheaper to have shipped our cattle across the bridge at $2.50 a carload but we did not like the idea of depending on the railroad in any way.

Crossing the “Great Colorado Desert” - March 1890

We soon got all our cattle together on the California side and were ready to move. All were glad to get away from Yuma and take our chance on “The Great Colorado Desert,” as it was then called. We followed the river and met a man named Carter, who had a small cattle ranch, from whom we bought half a beef that he had just killed. Our cattle were too poor for beef and a while beef was more than we could haul, and as the days were warm, we were afraid it would spoil before we could eat it.

Carter was said to know the desert well and I tried to hire him as a guide and offered him $20 a day to show us where the water was on the desert. He said, “He had not been out there for some time. Sometimes there was plenty of water out there and often no water as it depended entirely on whether there had been rain.”

We decided that Mr. Carter was probably right about the water on the desert and what we saw afterwards confirmed that opinion. We did not travel very far down the river before we were overtaken by two young men with four or five very thin horses. They said their name was Fox, that they were brothers, and that they had been following us for some time and were anxious to cross the desert and heard we were driving the cattle across to California and asked if we could not give them a job to help drive our cattle.

Tom Turner told them we had plenty of help as the cattle were getting very gentle and we had all the men we needed. Tom and I then had a talk and we decided to let them go with us as they said they were afraid to cross the desert alone as they knew nothing about the country. We told them if they were willing to help us we would let them go along with us. Tom told them that they could turn their horses in the “Remuda” (loose horses) and he would let them ride some of our mules which came from the Warner Ranch.

A Fortuitous Meeting - March 1890

We followed the old stage road down to where it left the river. I have forgotten the exact distance, but it could not have been over 20 miles. In this place there was quite a lagoon of water, so we camped there. Next day Tom and I followed the old road out into the desert looking for water for our next camp. We rode a good ways that day and came back to camp late quite discouraged as owing to the poor condition our cattle we were afraid of driving them a long distance without water. When we reached camp we were surprised to find several tents pitched close to us on the lagoon. We immediately inquired of our men as to who the people were. They did not know but thought they were engineers of some kind. Tom and I went over to see and introduced ourselves to the head man.

He proved to be D. K. Allen a civil engineer who told us he was making a preliminary survey for a railroad from Encinado [Ensenada], Lower California to Yuma and he had been out in the desert all winter. We then told him our anxiety about finding water and he assured us there was plenty of water on the desert and that the first water we would find was only 17 miles from our present camp. This he said was not sufficient for all our cattle, but further on about 10 miles just across the line near the boundary monument on New River there was quite a large charca in the channel of the New River which would probably water all the cattle for a week.

While we were at his camp the cook was preparing supper and we asked him what he was cooking. He said it was rattlesnake and he invited us to partake of it. We passed it along to all our crew who had called on Mr. Allen, as people were so scarce in that country they were as much interested in meeting someone as we were. The only man among us who tasted it was Jesus Maria Elias, who told us that when he was with General Crook as his chief trailer he had frequently eaten it. I knew Elias and his family well, but I never knew he was so celebrated a man as he really was.

I afterwards learned that he was the leader of the celebrated so-called “Camp Grant Massacre.” He with William Oury, eight Americans, quite a number of Mexicans and a large number of Papago Indians marched over to the mouth of Aravaipa Canyon, which was right in sight of the old Camp Grant but then occupied by American troops and nearly exterminated that band of Apaches. They killed all but the children whom they brought to Tucson as prisoners. The cause of this expedition was the constant raids of the Apaches against the settlers on the San Pedro and Santa Cruz rivers.

Calexico and New River - March 1890

The next afternoon we bid goodbye to Mr. Allen and the Colorado Valley and drove out 10 miles and camped for the night. The next morning early we were on our way and about afternoon reached the first watering place that Mr. Allen had referred to. After looking at it we decided we would only be able to water the weakest of the cattle. We had held the cattle back some distance from this water and Turner and I went ahead and looked at it as we were afraid the cattle would make a rush for the water. We cut our herd in two. As the stronger cattle were ahead on the road, we drove them on and let the weaker ones have the water.

About dark that night we reached the second watering place. This was near the New River stage station on the old overland road, but just across the line. This is the present site of the town of Calexico. We were quite pleased at the looks of what we could see of the country thereabouts. The mesquite was beginning to bud out with plenty of old grass around. The grass is commonly called guayella. The green shoots grow out of the old roots with a head like timothy. Also there was a great deal of what cattlemen call the “careless-weed.” All the cattle ate heartily and enjoyed their first good feed for some days. We concluded to stay for several days. And give our cattle a chance to rest.

Indian Wells - March 1890

The next day Turner and I thought we would take a ride over to Indian Wells, the next watering place. We easily found the water and the ruins of the old stage station. This is near what is called Signal Mountain, a very peculiar peak the only one I saw in the desert as the country all around is very level. The water at Indian Wells was in a round basin with mesquite trees growing all around it. While we were there Turner’s horse was taken sick and seemed to be in considerable pain. We laid down under a tree to rest. I soon fell asleep. Some kind of bird cried over my head and made a noise like a rattler.

Turner afterwards told me it was a catbird. I don’t know what it was, but at the time I nearly jumped into the water. As it was getting late we concluded we had better be getting back to camp. We decided to leave Turner’s horse there so we tied him up. I was riding a little horse which although small proved to have plenty of endurance. We put both our saddles on my horse one on top of the other. We took turns riding. One would ride ahead, then dismount and walk, leaving the horse for the one on foot to catch up to and ride. Alternating this way we had no difficulty in getting back to camp.

On to Carrizo Creek - March 1890

From our camp at New River we drove to Indian Wells, north of Signal Mountain. Late the next day we started for Carrizo Creek which makes the western boundary of the desert. This was the longest drive without water we had to make crossing the Colorado Desert. I think it was 40 miles. Our cattle had done well while camped at New River as there was more pasture for them there than at any place on the trail since we left the Empire Ranch. The country was open so we loose herded them. Strange to say the only steers we lost on the desert were drowned in the charco at New River. The reader may remember we turned our cattle loose the night we arrived there. The two steers were young and very weak and probably got their feet fast in the mud in the middle of the pool. We drove frequently at night as the days were warm on the desert. We hung a lantern on the tall board of our wagon and our lead steers would follow it like soldiers. Before we reached Yuma only one man was necessary on guard so we changed every three hours which gave the men more sleep, but it was rather a lonesome job for the fellow that had to watch the cattle.

Carrizo Creek - March 1890

When we reached Carrizo we found a shallow stream of water in a wash the banks of which were white with alkali. Not only the stream but the hills, barren of all vegetation, were full of the same substance. I never saw a more desolate place in my life. In all of Arizona there is nothing to compare with it that I know of.

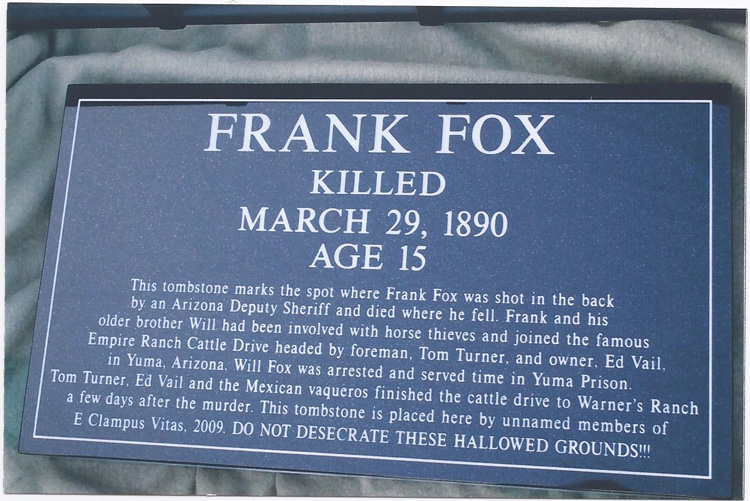

The next morning the cattle were scattered up and down the creek most of them lying down and a few of them eating what little salt grass they could find. They had come through all right from our last camp, except one young steer that could not get up. We tried to lift him on his feet but he could not stand so I told the boys I was going out to see if I could find bunch grass along the hills and the youngest of the Fox brothers offered to go with me. He was a good looking young man, nearly six feet tall and about 20 years old I should think. His brother was a rather short and heavily built. These boys had worked cheerfully since they met us and were on good terms with all our men.

The Sheriff’s Unexpected Arrival - March 1890

Young Fox and I found some grass and brought it to the sick steer. Fox was a pleasant young fellow and said that Tom Turner had offered to give them work on the Empire Ranch if they would go back there with our men. A little later was surprised to see a carriage with four men in it coming toward our camp from the west. One of the men beckoned to me and I walked over to see what they wanted and who they were. They were the first people we had seen since we left the Colorado River, about a hundred miles back. He said he was a sheriff from Arizona and as he spoke, I recognized him. He then asked if we had two Americans with us who joined us near Yuma, and I replied that we had. Then he introduced me to the other three men, one of whom was his deputy and the other, his driver, who was from Temecula, California, and I think he said a deputy sheriff there. The fourth man, the sheriff told me came with him from Arizona and was the owner of some horses which he said the Fox boys had stolen from his ranch. The sheriff then told me that he and his deputy had followed the Fox brothers all the way to Yuma and then they had followed our trail after the boys until we crossed the line. They then returned to Yuma and took the train for California, as he could not go into Mexico.

A Tragic Ending - March 1890

As nearly as I remember I said: “Sheriff, you know the reputation of our outfit; it has never protected a horse thief and has always tried to assist an officer in the discharge of his duty.” I also told the sheriff that the boys had done the best they could to help us in crossing the desert and that I was sorry to hear they were in trouble. I felt it was my duty to tell him that the boys were well armed and quick with a gun. “You have plenty of men to take them,” I said. “Be careful. I don’t want anybody hurt.” The sheriff answered, “If they ask you anything, tell them that we are mining men going out to look at a mine.”

I knew if the boys were sure that the men were officers there would be bloodshed at once. It was a very unpleasant position for me as I really felt a good deal of sympathy for the brothers and I knew them to be young and reckless. The older one came to me and said, “Who are those men and what do they want?”

I had to tell him what the sheriff told me to say: viz, that they said they were mining men out to look at a mine near there. I could see he was not satisfied and was still anxiously watching the sheriff’s party.

Very soon after I was standing on one side of the chuck wagon, the elder brother was leaning against the back and his brother near the front wheel on the opposite side of the wagon from me. Suddenly I heard a scuffle and when I looked up I saw the sheriff and another man grab the elder boy and take his gun. His deputy and assistant were holding his brother on the other side of the wagon. They had quite a struggle and young Fox pulled away from them, ran around the wagon past me with the deputy in pursuit. He ran about a hundred yards up a sandy gulch and the deputy was quite close to the boy when he raised his gun and fired. Young Fox dropped and never moved again. I was close behind the deputy as I had followed them. When the latter turned toward me with his six-shooter still smoking and he was wiping it with his handkerchief. “I hated to do it,” he said, “but you have to sometimes.”

A Proper Burial - March 1890

I was angry and shocked at his act, as I had never seen a man shot in the back before. I then saw the other Fox boy walking toward his brother’s body, which was still lying on the ground. The officers who had him handcuffed tried to detain him, but he said, “Shoot me if you like, but I am going to my brother.” He walked over to where the body lay and looked at it. Then he asked me if we would bury his brother and I told him he could depend on us to do so.

Then I told the sheriff there was no excuse for killing the boy as he could not get away in that kind of country. He replied that he was very sorry about what had happened but said, “You know, Vail, that I got my man without killing him, and that it was impossible for me to prevent it, as I had my hands full with the other fellow at the time.”

Tom Turner was not in camp when this happened as he had gone out around the cattle. The sheriff and his posse left shortly after and took their prisoner with them, but they left the body of young Fox lying on the ground where he fell. We dug a grave and, wrapping the young man’s body in his blanket, buried him near the place where he fell. It was the best we could do. I saw a man in Tucson last week who told me he was at Carrizo Creek a few years ago where he saw the grave which had a marker with the inscription, “Murdered.”

Carrizo Creek to Warner Ranch - March 1890

We were glad to leave Carrizo the next morning and be on the way to Warner Ranch. The country was dry and barren until we reached Vallecito creek, which is in a pretty little valley with some green grass growing in it. Between there and Warner, we passed the San Felipe Ranch and from there on to Warner the road ran through a better country for cattle. Finally we reached Warner Ranch and it looked good to us and I have no doubt our horses and cattle enjoyed the sight of it as much as we did. The grass was six to eight inches high and as green as a wheat field all over the ranch, which covers about 50,000 acres.

We had been about two months and ten days on the trail since we left the Empire Ranch. There was not a man sick on the trip that I remember. We had slept on the ground all the way except at Yuma for a few nights when our blankets were in the wagon across the river. Our men had been loyal and cheerful all the time and I am glad to have all them share with Tom Turner and myself in the success of our drive. After we reached Warner, the Justice of the Peace sent for men and inquired about the trouble at Carrizo Creek. I told him what I saw just as I have related it in this diary, he then told me that the officers were out of their jurisdiction in California as they had no papers from the California Governor at that time, but I believed they obtained them later.

Some Well-Deserved R&R - April 1890

We had to hold the herd for a few days until they were counted and received. Most of our men were at liberty and we all went to the Warner Hot Springs and took baths which all enjoyed. The Indian women seemed to be always washing clothes and our men would join the group and wash their own and sometimes borrow the soap from the Indian girls. There was a good deal of laughing and joking in Spanish during the performance. The water was as it comes out of the ground is hot enough to cook an egg. Close and by running parallel to it is a stream of clear cold water.

Very soon all the cowboys were sent to Los Angeles where they remained for a few days to see the sights of the largest city they had ever visited, but after a short time they said their legs and feet were sore from walking and that they were all right on horseback but no good on foot, so we shipped them back to Tucson and the ranch.

The S.P. Capitulates - 1890

A short time after our return, a meeting of cattlemen was called at the Palace Hotel (now the Occidental) then owned by Marsh & Driscoll who were at that time among the largest cattle owners in Arizona. The object of the meeting was to consider the matter of establishing a safe trail from here to California for cattle. From our experience I was able to make some suggestions, viz: To build a flat boat to ferry cattle across the Colorado River. To clear out the wells at the old stage stations on the Colorado Desert and put in tanks and watering troughs at each of them and if necessary to dig or drill more wells. Without delay all the money necessary for this work was subscribed.

The Southern Pacific Railroad Company when they heard of the proposed meeting asked permission to send a representative and the cattle association notified the company that the cattlemen would be pleased to have them do so. Therefore the S.P. agent at Tucson was present. Soon after our cattle meeting, we received an official letter from the S. P. Company at the Empire Ranch saying that if we would make no more drives, the old freight rate would be restored on stock cattle. The company kept its promise and it held for many years. Therefore the trail improvements were never made.

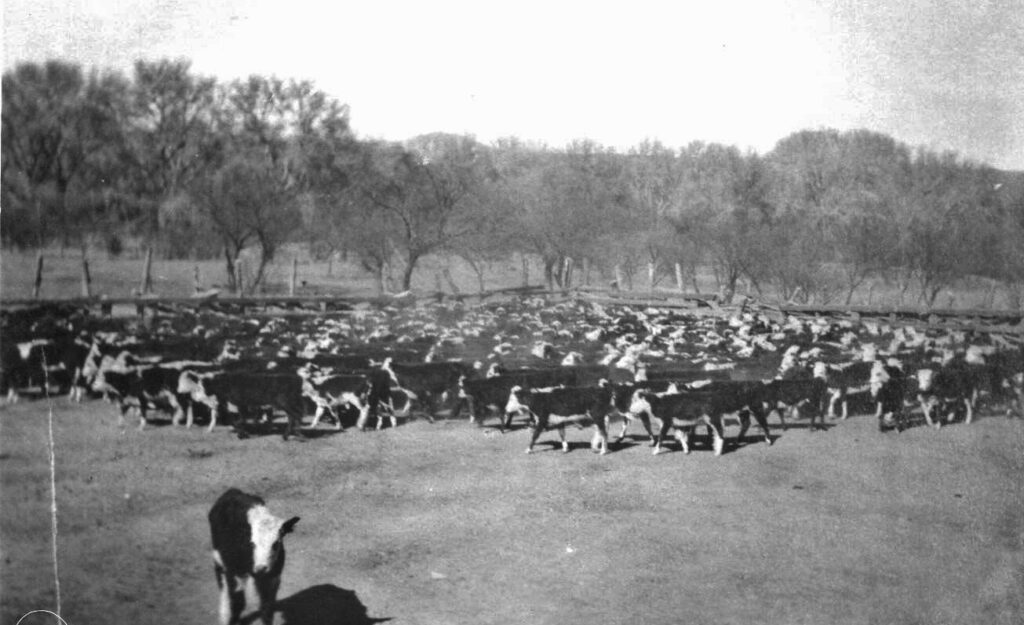

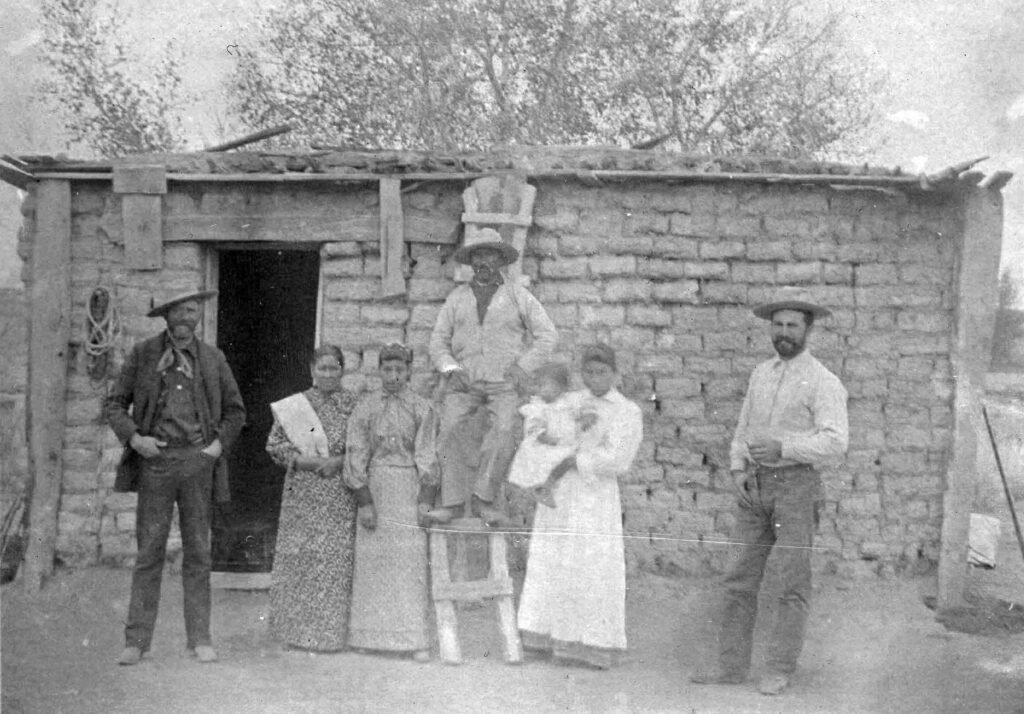

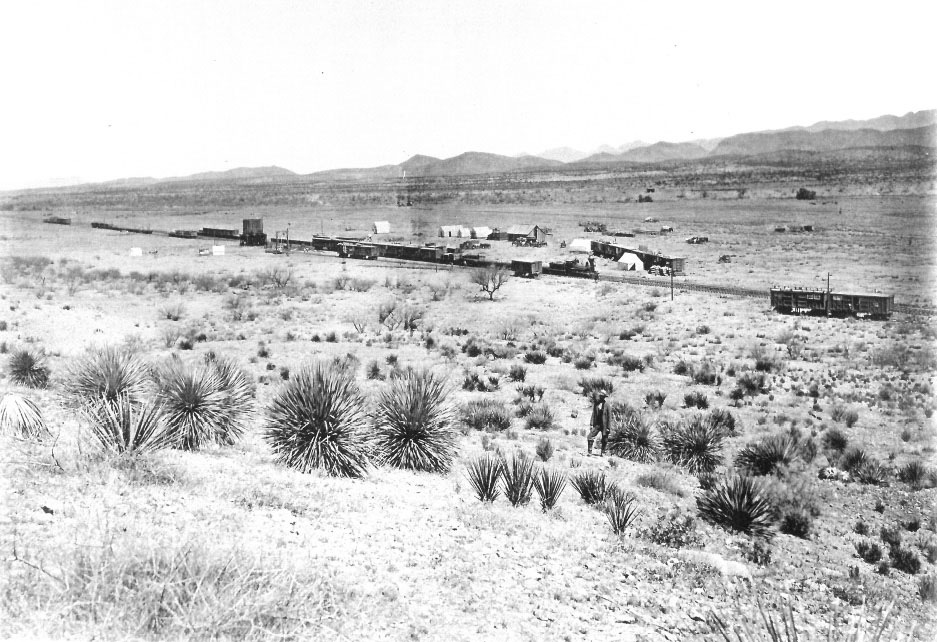

Drought - 1890

Fred Paine, a California cattle buyer, wrote about his cattle buying expedition in the 1890’s when he found the area in the grip of a drought. He arrived at the railway shipping point of Pantano, about twenty miles east of Tucson, and found an ordinary station house and a small wooden shack about a hundred yards away, about 10’ x 12’. These were the “shipping yards” from which most of the Empire cattle were loaded out. Jim Brady was the proprietor of the shack, which was connected by telephone with the Empire Ranch. He served coffee and a shot or two of very raw whiskey for breakfast but was cordial to the new arrival. Bradly was a soldier who had served in Arizona and elected to stay there when his service was finished. Paine left this establishment for the Empire Ranch to meet with Tom Turner, the foreman, whom he knew. The road led through a gap in a small mountain range, and then down a gently sloping and rolling country, past several deserted houses, and to the ranch house which was about twenty miles from the railroad.

From the ranch house, Paine left for the round-up camp, but first climbed a nearby hill to size up the surroundings. ”The mountains were most too far away to call this a valley, the ranges being fifteen or twenty miles apart. Between were gently rolling hills with a little oak brush here and there. It looked like a big country.” He noted that the cattle were in very poor condition, understandable since there was no grass in sight. Many starved to death and died, but on the vast acreage of the ranch, many survived until the rains fell again. ” Scattered over an immense range they browsed on the oak bushes, gnawed on the grass roots and I saw, later, twelve thousand head rounded up in one bunch after they got enough strength to stand handling. After dying by the thousands and shipping out train load after train load, we still found about twenty thousand head after grass came.”

Gila Monster Bite - May 1890

Edward Vail wrote to his father on May 4th: “I was afraid you may have heard reports in the papers about Walter having been bitten by a Gila monster. It happened at the Happy Valley where they were branding last Friday. I am glad to say he is alright and will go home to the Empire today. Walter found the reptile while riding and wishing to show it to Mr. Gates who was in camp killed it as he supposed and tied it to the back of his saddle. When he put his hand back to get off the brute seized the middle finger of his right hand and he had to call for help to get its mouth open. Walter tied the finger tight about the wound and then cut it open and put it in carbolic acid and started alone for Pantano. Dr. Handy met him there and we came in at once to Tucson on a locomotive. Walter was in great pain and at 6 o’clock that evening his tongue and throat were so swollen that he could scarcely speak – he suffered great agony at times but after 9 p.m. began to improve and slept well the balance of the night. Dr. Handy is greatly interested in the case as in previous cases the bite of a Gila monster has proven fatal. Maggie and I came in with Walter and were of course very anxious, but he now feels all right.”

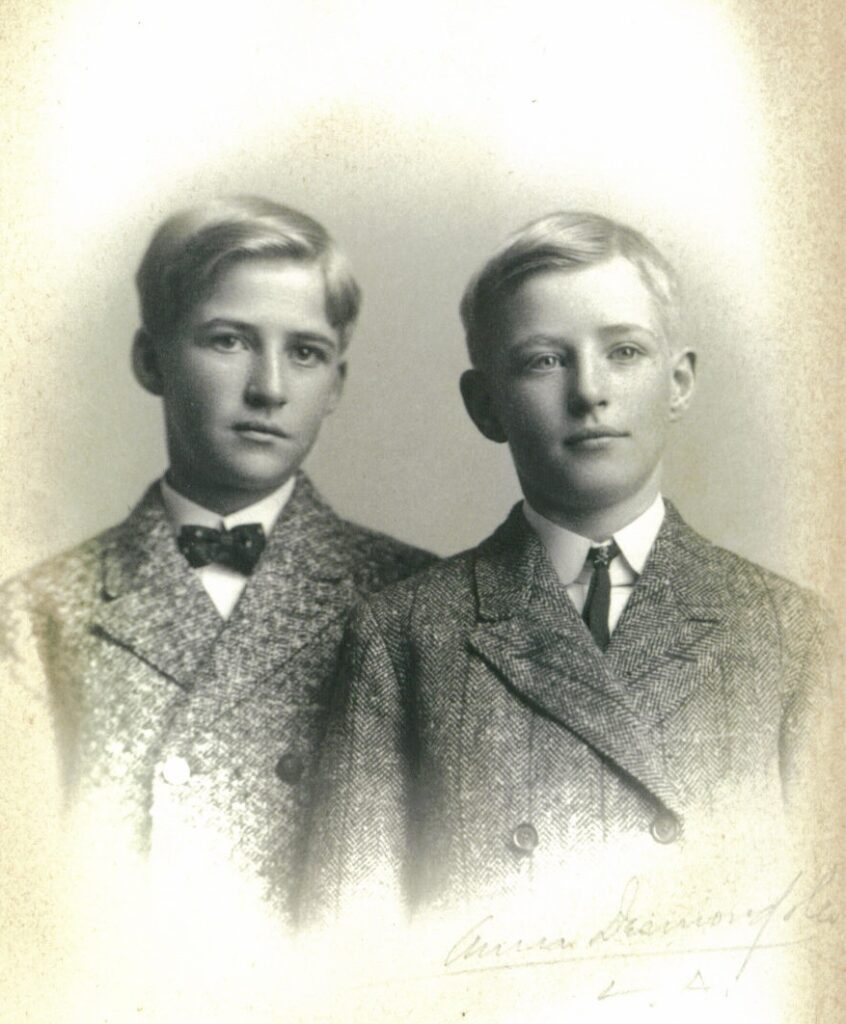

Mahlon Vail is born - November 1890

Mahlon Vail, who was named after Walter Vail’s father, was born in Tucson on November 30, 1890. Mahlon was the only Vail child not born in New Jersey or Los Angeles. Maybe Margaret wanted to celebrate Thanksgiving at the Empire Ranch and did not make it to Los Angeles in time for the birth. The family now consisted of four boys and one girl.

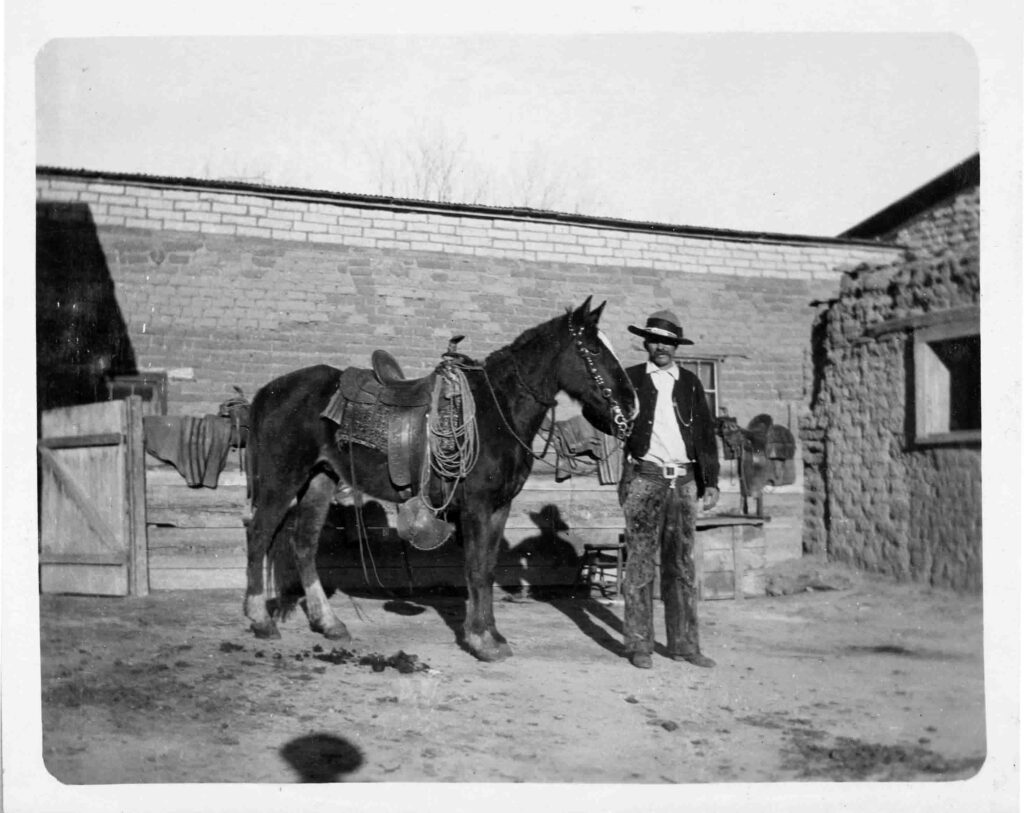

Good Horses - February 1891

Good horses played a critical role in ranching operations and transportation. Walter Vail discussed the thoroughbreds he had purchased to improve his stock. “My horses are doing very well. I have been raising ordinary horses… for saddle use. I am going in to raise fine horses now. I have two Rise Dike Hambletonians stallions. Both are on the herd book. I have a four-year old from Sultan raised by L. J. Rose. He was sired by Sultan. He is on the herd book as Sir Richard. Ben Bolt and he will trot a mile together in 2:50. I am breeding these small horses because they are better saddle horses and travelers.” [Arizona Weekly Citizen, 1/19/1884].

In 1891 there were several newspaper reports of Vail horses participating in horse races, including “Sleepy John” who was sold that year for $250 to General Royal A. Johnson. Horse racing did not become a serious preoccupation for Walter Vail – no doubt ranching and Total Wreck mine operations kept him too busy.

Wild Carriage Ride - April 1891

Walter Vail was reputed to be a fine “four in hand” driver and he loved speed. His passengers not so much. There are several stories of his driving adventures: “Walter Vail, Mr. and Mrs. Gage, and R.R. Richardson came in town yesterday with Walters fine four-in-hand. They had a fine dash along the road. Things looked queer for a time and Walter says he would give a thousand dollars for a photo of their looks at one time. This thing of driving four spirited horses to a buckboard with three lines on the ground and only one line in hand is not exactly to the taste of the remainder of the party even if Walter does like it. Mrs. Gage stuck to her seat but Mr. Gage was missing but soon turned up and without injury It was no child’s play for some time but fortunately wound up with but little damage and no one injured. In keeping company with Walter, it would evidently be advisable to take out a life or accident insurance or not go.” [Arizona Republic, 4/11/1891].

Maggie at Warner’s Ranch - September 1891

Margaret, Walter, and their infant son Mahlon spent several weeks at Warner’s Ranch while Walter helped with the cattle roundup and sale. Margaret wrote to her two oldest sons, Russ and Walter Jr.: “Here we have been for almost two weeks. We have camped over at the hot springs most of the time in a little old adobe house… We had no stove so did our cooking in the fireplace. We wished very much you could have been with us. I am sure you would have enjoyed it. The water was splendid. You can see it coming up at the bottom of the brook bubbling like a pot of boiling water – so hot you cannot see your hand in it. Papa drove us to Julian which is an old mining camp. We stayed there all night and drove home next morning. The camp is right on top of the mountains. we could see the desert and the Salton lake.”

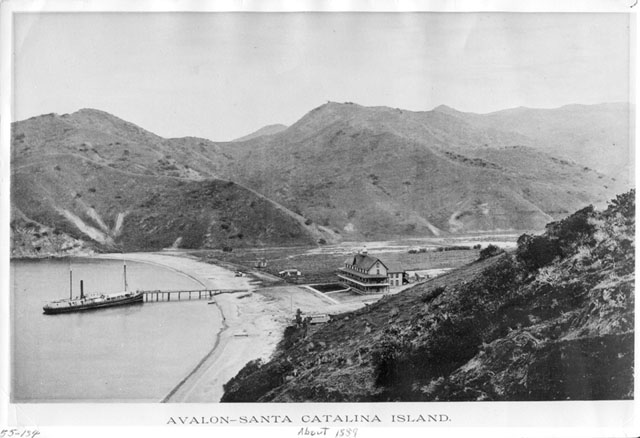

Catalina Island - 1892

By 1892 Vail and Gates had further expanded their California grazing areas by leasing Santa Catalina Island from the Banning brothers. He first had to remove the sheep that had been raised on the island. [Tombstone Weekly Epitaph, 7/3/1892]

Harry Heffner, who became manager of the Empire Ranch from 1902-1905, was first hired by Walter Vail in 1893 to gather cattle on Catalina for shipment to Kansas. He had never worked in ranching, just knew how to ride a horse. Heffner recalls Vail saying: “We’re gathering cattle on Catalina Island. We’re going to take them off because they are starving to death over there. We’ll try you out over there. See if you can help the boys gather them. We’re going to bring them to the Mainland and ship them to Kansas; put them on feed up there and try to get them fleshy enough so we can sell them.'” The cattle were moved by barge to San Pedro and were then taken to the Centinela Ranch, owned by Daniel Freeman, to be fed before loading them onto railway stock cars. [Harry Heffner oral history, 1960]

Edward Newhall Vail - December 1892

Edward Newhall Vail was born on December 8, 1892 in Los Angeles. He was named after Walter Vail’s brother, Edward “Ned” Vail. And his middle name – Newhall – was Margaret Vail’s maiden name. Edward Newhall’s family called Ned “Uncle Nedie.” He was also known as “Tio,” the Spanish word for Uncle.

Arizona Livestock Sanitary Commission - 1893

In February Walter Vail was appointed to the Arizona Livestock Sanitary Commission (later renamed Livestock Sanitary Board). The Commission was responsible for recommending cattle industry regulations to the Governor and Legislature. Important issues dealt with during Vail’s term included the registration and inspection of brands – the first Territorial brand was recorded on April 28, 1897. The Commission/Board also recommended quarantine measures to prevent the spread of Texas Fever (or Southern Cattle tick) in Arizona.

Walter Vail’s Views on Prosperity in the Southwest - September 1893

An interview in the San Francisco Chronicle (9/16/1893) documents Walter Vail’s view of the cattle industry: “The veteran cattleman has recently been over his ranges. He says that now the cattle are fat and In good condition in every way. Grass has lately been better than for a long time previous and all the cattlemen are on a much better basis than formerly. For two or three years past drought has affected nearly all parts of Arizona but it is different now. Of all the different industries said Mr. Vail during these dull times I only know one that has kept up and been prosperous That is cattle-raising or at least the price of beef. It has not fallen at all. From what I can see too the cattle business is destined to be much more prosperous during the next few years than It has been. All things point that way.”

Vail also explained his strategy from breeding cattle for finishing elsewhere: “We raise and ship cattle to Iowa, Kansas, and Montana principally. The Iowa and Kansas people get them at three years old to fatten with corn and Montana cattlemen get them at two years old to run on their ranges They take on weight rapidly on the northern grass. Of course, they must get there when the grass is new. It is very strengthening and fat-producing as it gets older.”

Partnering with the CCC - 1894

In 1894 Vail and Gates purchased stock in the Chiricahua Cattle Company (CCC), which operated to the east of the Empire in the Sulphur Springs Valley. They had partnered before with J. V. Vickers, who owned the controlling interest in the CCC. Vail, Gates, and Vickers established the Panhandle Pasture Company, and bought seven thousand acres of grassland in Sherman County, Texas, and an equal amount across the line in Beaver County, Indian Territory [later Oklahoma). The Empire and the CCC each shipped their stock as yearlings and two-year-olds to the Panhandle, ranged them from one to two years, then sold the fattened steers direct to slaughterhouses. Each company conducted its business transactions separately, kept separate financial records, and operated as autonomous cattie companies using mutual rangeland. [Dowell, Gregory. History of the Empire Ranch, 1978]

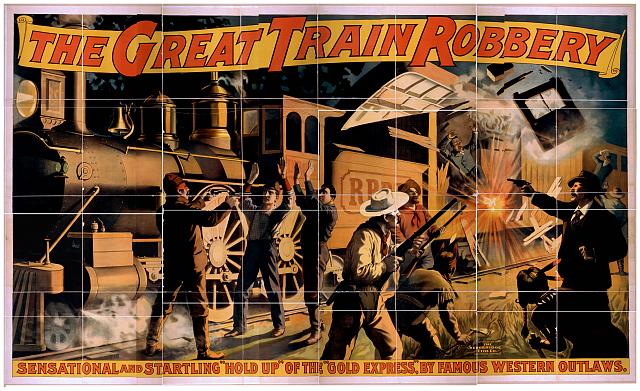

Walter Vail: Storyteller - July 1894

In July 1894 Walter Vail told an amusing story about himself in the Arizona Daily Star. “Along about 1885, you remember, two trains were held up at Pantano in so many weeks. I was then making some shipments of cattle to southern California. It happened that a few days alter the first hold-up I went to Los Angeles with a lot of steers, myself and men dressed in the conventional cowboy style. Somehow we were regarded a little bit suspiciously about town. We returned to the ranch, gathered more stock and appeared in Los Angeles about two days after the second hold-up. “A few people in the Angel city knew my ranch was only a short distance from the scene of the two daring robberies, and somehow Mr. Brooks, who was then United States marshal for the southern district of California, got it into bis head that I and my men were the real train robbers. We met Jim Millus, an old friend of mine, who is always ready for fun, and who told Marshal Brooks that we would bear watching. “Pretty soon I noticed that two men were following me wherever I went. I had sent my men to Catalina island, and was the only one of the Empire ranch force in the town. For four days these fellows camped on my trail. No matter where I went, I saw them. “Finally, I met Marshal Brooks and Jim Millus in a popular resort. When I entered the place, Jim grasped me by the hand and introduced me to Brooks, who looked bewildered, Jim saying that I was an old-time friend of his. About this time my shadowers appeared on the scene and looked as if they would fall through the floor. “Matters were explained and the laugh was on Brooks, who took the joke good naturedly. He confessed that he had had the place where I was sleeping, on Broadway, under surveillance for four nights before, and that he had officers shadow my men till they left San Pedro on a little steamer for Catalina islands.”

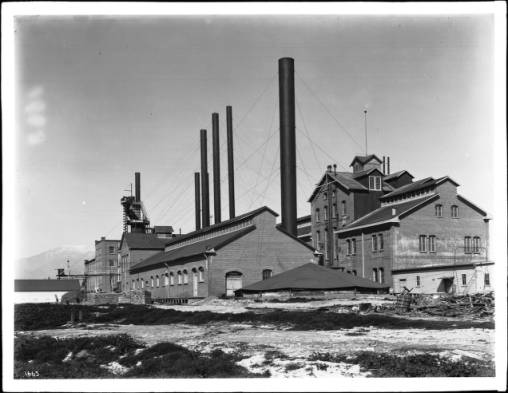

Chino Ranch Co., California - January 1895

In 1895 the Chino Ranch Company was incorporated. Vail and Gates along with three other California investors were the incorporators. Walter Vail had been working with Richard Gird, an Arizona pioneer and one of the founders of Tombstone, who had purchased the forty-seven thousand-acre Rancho del Chino, east of Los Angeles. Gird established the Chino Beet Sugar Factory and in 1891 he persuaded Vail to try the beet pulp by-product of the sugar refining process as cattle feed. The experiment was successful and was especially valuable during the 1890 drought years.

In addition to their cattle and landed interests, the Chino Ranch Co. owned the townsite of Chino, which included over 1,000 lots that were quite valuable as the town had a population of about 1,500 people. Adjoining the town of Chino they owned 1,500 acres of sugar beet and alfalfa land on which they had a fine herd of standard-bred and registered draft horses, formerly owned by Richard Gird.

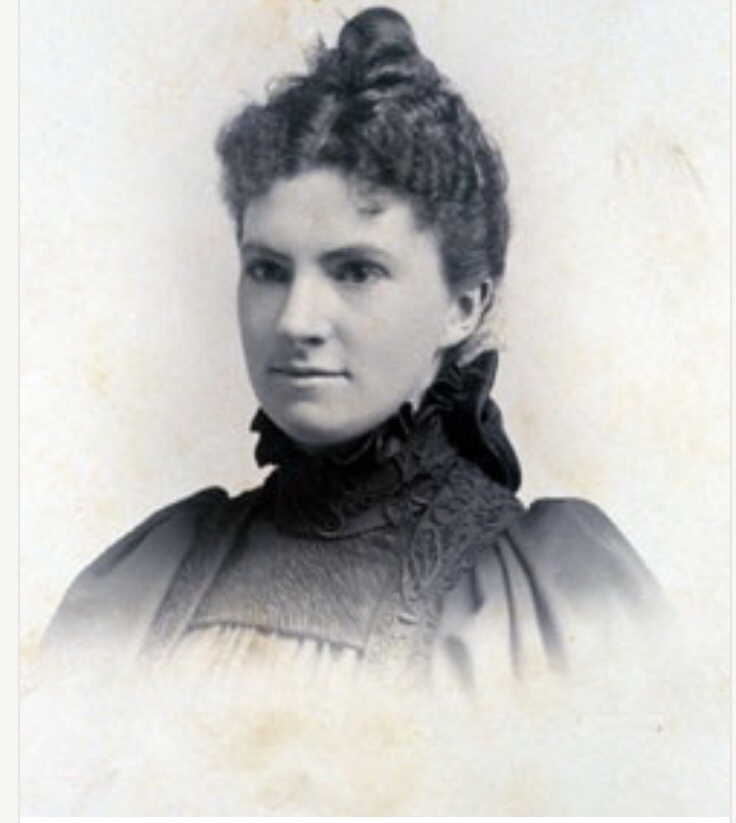

Charlotte Newhall and Sinclair Oliver Marry - March 1895

On March 20, 1895 Margaret Vail’s sister, Charlotte Newhall married Sinclair Oliver in Los Angeles. The ceremony was held at the home of Margaret and Charlotte’s mother, Mary Jane Newhall. Margaret had wanted her mother to move West from New Jersey and sometime in the early 1890s Mary Jane along with Margaret’s two brothers, Isaac and Edward, and sister Charlotte relocated to Los Angeles.

Sinclair Oliver had become the confidential secretary to Vail and Gates in 1891. The couple took a honeymoon trip to San Francisco and were to make their home at the Empire Ranch. Sadly, Sinclair died in August. He had moved to Arizona from New York seeking a cure for a “fatal disease,” perhaps tuberculosis. Charlotte returned to Los Angeles where she worked as a hair specialist in a hair dressing salon.

Burlington Avenue Home - November 1895

An announcement in the Los Angeles Times [11/15/1895] noted: “Plans are being drawn for the placing of a story underneath the residence of Walter Vail on Burlington Avenue, south of Seventh street, and for refitting the buildings with hardwood. The new part will contain six rooms and cost several thousand dollars.”

The Vail family numbered 8 in 1895: Walter, Margaret, 5 sons and one daughter. Up to that point the children had been home-schooled at the Empire Ranch by various English governesses. “McGuffey’s readers and Hilliard’s readers with their stress on elocution and formal discourse were mastered, and after the Sunday Bible readings given by Margaret Vail. The children were free to ride about the countryside on their ponies. This idyllic life was permanently interrupted when Mahlon shied a boot at an English governess and she left in a huff.” [Christine Shirley manuscript, 1977]

The Family and Corporate Headquarters Move to Los Angeles - 1896

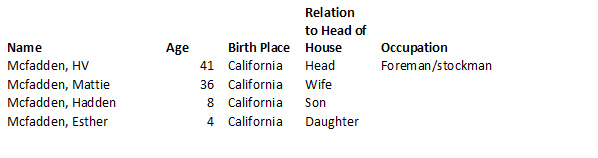

In the summer of 1896, the Vail family made Los Angeles their home. The corporate headquarters of the Empire Land and Cattle Company had been moved to Los Angeles a few years earlier. The Empire Ranch was left under the management of Hadden McFadden. He hailed from the San Luis Obispo area of California where he had farmed. His wife Martha and son and daughter Perry and Esther (who went by “Tommy” lived with him on the Empire Ranch.

Margaret Russell Vail - November 1896

Margaret Russell Vail, the last of Margaret and Walter’s seven children, was born in Los Angeles on November 13, 1896. She was named after her mother and was called Margie. Her middle name was the maiden name of her maternal grandmother, Mary Jane Russell Newhall.

Walter Vail’s Accident at the Empire Ranch - August 1897

Walter traveled between Los Angeles and Arizona frequently after the family’s move to Los Angeles. In the summer the whole family would spend time at the Empire. Walter wrote to his father [8-16-1897] about an encounter he had with a bull. “Two weeks ago tomorrow Mr. Gates and myself rode down to the large pasture in the cienega to look at some bulls we bought last year in Kansas, and which had recently arrived from there. On the way to the pasture we met Oscar Ashburn who has charge of the cattle for us on the San Pedro river, and as Mr. Gates was anxious to talk with Ashburn I changed places with him and took his horse, not knowing that it was half broken. I rode around the pasture with Russ and Walter and we were driving the bulls to the corral when I discovered one that was very lame in the front foot, and as thought there was a snag or nail between his claws told the vaqueros to throw him so we could doctor him. They threw their ropes but missed the bull. He came around my way and I lassoed him with a big grass rope that was on the saddle. The horse not being accustomed to hold and the bull being very heavy he started bucking. I held the bull and stayed on the horse until he fell with me. The second time he fell the bull ran behind my horse and as the end of the rope had caught to the horn of the saddle so it would not come loose he tied me down on the saddle; and as the horse bucked very hard it struck me on the horn of the saddle over the heart, gave me a knock-out blow and I became unconscious and I fell off. The horse then kicked me in several places the worse one was a severe kick I received on the inside of the leg alongside of the shin bone.

I remained at the ranch thinking it would get better there, but it did not, so I concluded to come to Los Angeles where I could get good medical care and treatment. I arrived night before last and as soon as I got here Dr. Worthington opened the leg and took out a great deal of bruised blood, as the main vein in the leg had been entirely severed with the kick, and the bruised parts had filled with blood. Of course, as you can understand it is rather painful sometimes and a recovery may be somewhat slower than I first thought.”

Blackleg Disease - 1898

In 1898 cattle growers in Arizona and California encountered outbreaks and blackleg (bacillus anthracis emphysematosa). The germ of blackleg generally enters through small wounds in the skin caused by barbed wire, stubbles, thorns, burrs, etc. and primarily affects yearlings. Both states imposed regional or local quarantines which prevented the sale of cattle.

The Pasteur Blackleg Vaccine had been in use in Europe for a number of years and starting in 1895 it was used experimentally in Western states. Arizona’s Territorial Veterinarian, James C. Norton was actively promoting use of the vaccine which at the time cost about 12 cents per dose. Vail and Gates lobbied for the distribution of the vaccine, free of charge, by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The 1908 Brands and Marks publication by the Arizona Livestock Sanitary Board notes that the vaccine was available free of charge at that time.

Interest in Santa Rosa Island - March 1898

Starting in 1898 Vail & Gates began to investigate the possibility of purchasing Santa Rosa Island, off the coast of Santa Barbara, CA. From 1881 to 1893 the island was solely owned by Alex P. More. When More died in 1893, he left his estate to his sole surviving brother, John F. More, four sisters, and ten nieces and nephews.

The real estate firm of Farnsworth, Vail & Calkins wrote to Vail & Gates in March 1898 to advise them of the valuation of the island. “The stock consists as follows: 2000 head of cattle; 25,000 head of sheep; also some 170 head of horses. We understand that the wharf is in good repair and practically new and there is some 60 miles of fencing in good repair. The improvements also consist of dwelling house, barns shearing sheds and dipping houses complete; all wagons, harness, etc. The stock has been renewed from time to time by the best animals procurable.” The estimated value of Santa Rosa Island was $273,103.

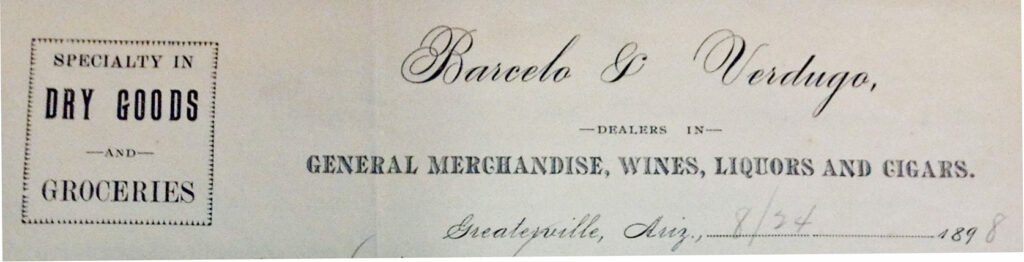

Personnel Problems - August 1898

A letter from Barcelo & Verdugo, proprietors of a general store in nearby Greaterville, responding to Empire Ranch foreman, Hadden McFadden, provides a glimpse into interactions between the Empire Ranch and a local community. “I must confess that the contents of you letter has greatly surprised us as you holley [sic] blame us for misconduct or wrongdoing of Jose Velaquez. This time when he came to our store he was intoxicated & get his liquor somewhere else; when I learned he was on some errand from the ranch I advised him to do his business immediately and return home. This he promised to do and I thought he had been to the ranch & perhaps returned as I have seen him here since and sober. Of course we thought he was here with your permission.”

The letter makes clear how important commerce with the Empire Ranch was. “As to Messrs. Vail & Gates we greatly appreciate their patronage and would do as we could on their behalf and would prefer to lose all we possess than to have trouble with these gentlemen whom have been so kind with us.”

That Scoundrel, G. G. Gillette - November 1898

In late November the cattle industry was rocked by the news that George Grant Gillette, the “cattle king” of Woodbine, Kansas, “busted owing people in all part of the country over a million dollars.” A charming and colorful character “He would buy thousands of cattle without ever seeing them and his success induced rich men to trust him with lots of money. He had, when he busted, 30,000 head of cattle, mortgaged two or three times, and had been feeding them at a cost of 1,000 per day.” [The Marquette Tribune, 12/1/1898] Gillette reportedly fled to Spain but was later found living with his family in Mexico.

Vail & Gates were among those affected, as Walter detailed in a letter [12/12/1898] to his brother Ned. “In regard to the Gillette failure, will say that in a way we were pretty seriously affected by it. At the same time Gillette did not get away with any of our money, but we no doubt will lose considerable profit on the cattle on account of his failure. We had sold him a trainload of CCC’s and heart cattle from the Panhandle ranch which amounted to about $18,000. On these cattle he paid us $1,500 and the freight which amounted to about $500; and was to have paid us the balance due, about $15,000 on December 1st which of course he did not do as he skipped out on the 23rd or 24th. Mr. Gates shipped about 4700 head of the J.A. cattle from Southard, Texas, to Strong City, Kansas for Gillette, but the cattle were billed to Geo. R. Barse who was to put up the money for Gillette to carry the cattle. These cattle never have been turned over to Gillette, and as he had paid $10,000 in cash on the cattle, we now have them in Kansas, on roughness, and Gillette’s $10,000. Of course it would have been much better if he had carried out his deals and paid us for the cattle as it would have relieved us of much worry and expense.”

While living in Mexico Gillette made a new fortune in mining. In 1904 he settled with his creditors and returned to the U.S. In 1908 he moved to Los Angeles, purchased a fine home, became involved in the California oil business and real estate, and continued to be involved in “shady” deals.

A Tragic Carriage Accident - February 1899

In February 1899 Captain William Banning was driving his father’s vintage stagecoach in Los Angeles with four passengers, including Walter Vail. When they reached Washington street and Grand Avenue Banning “attempted a turn which was too short for six horses The wheels struck the car track at the same time the coach was tilted to one side the kingbolt broke and the top of the coach toppled over throwing the occupants violently to the ground.” One passenger “was thrown against an electric light post the others falling on top of him. The shock caused heart failure and he died almost Instantly. Vail was pinned under the coach and suffered a fracture of the right leg between the knee and ankle.” [San Francisco Chronicle, 2/5/1899]

General Phineas T. Banning made his first fortune driving six-horse stages from what became the Port of Los Angeles on routes that led to San Bernardino and Fort Yuma, AZ.

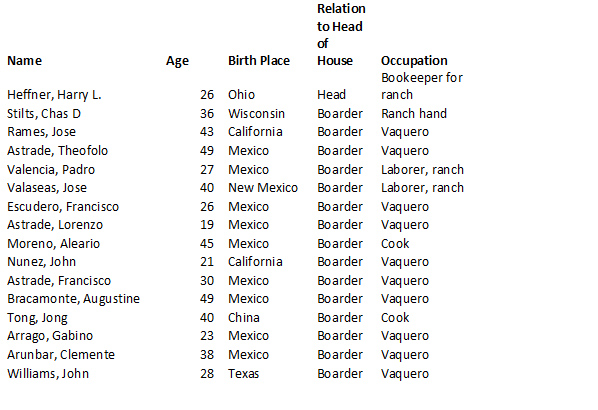

1900 U.S. Census

The 1900 U.S. Census provides an interesting view of Empire Ranch operations. At the Empire Ranch headquarters we find the McFadden family:

At the Rosemont section of the Empire Ranch we find a large grouping of vaqueros. The census was taken in June so it’s possible that some roundup operations were happening at Rosemont at the time.

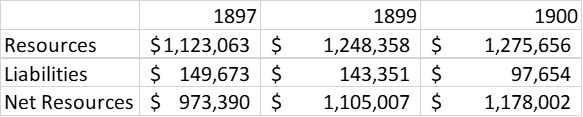

Vail & Gates Net Resources, 1897-1900

Three Statements of Resources & Liabilities for Vail Gates provide a view of the financial health of the corporation at the end of the 19th century.

The most significant resources listed in the 1900 statement included:

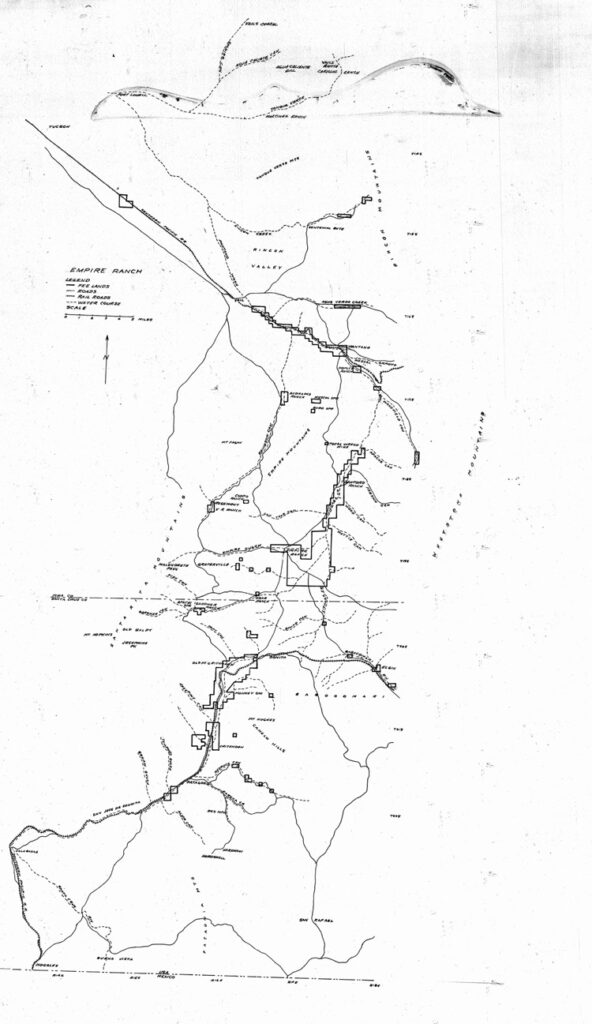

- 10,320 acres of patented lands, water rights, desert land claims, improvements, machinery, etc., range rights controlling 800,000 acres of government lands – $150,000

- 27,000 stock cattle in Arizona ($15) – $405,000

- 8,688 shares of Chiricahua Cattle Company stock ($30) – $260,640

- 5163 head of steer on Panhandle ranch ($25) – $129,075

Vail & Vickers Purchase Santa Rosa Island - June 1901

“The majority of interests in Santa Rosa island, which was owned for many years by the late A. P. More, was today sold to Walter L. Vail and J. V. Vickers, one of the largest cattle firms in the country, whose headquarters are in Los Angeles but whose large Interests are in Arizona, New Mexico and Texas. Santa Rosa island for many years has been one of the leading sheep and cattle ranges in the west. Vail & Vickers will stock the island to its full capacity.” [The Independent, Santa Barbara, CA, 6/22/1901] Carroll Gates chose not to participate in this investment.

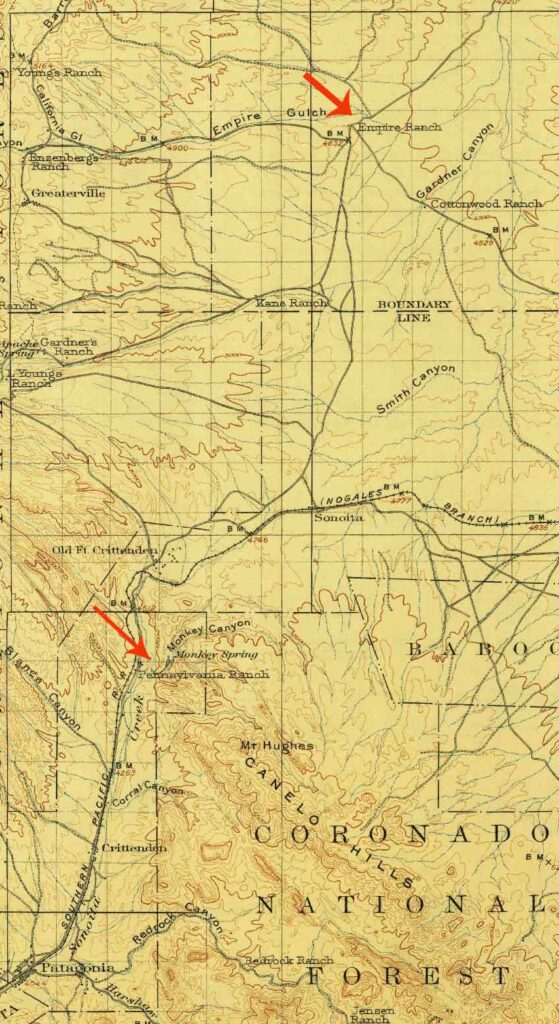

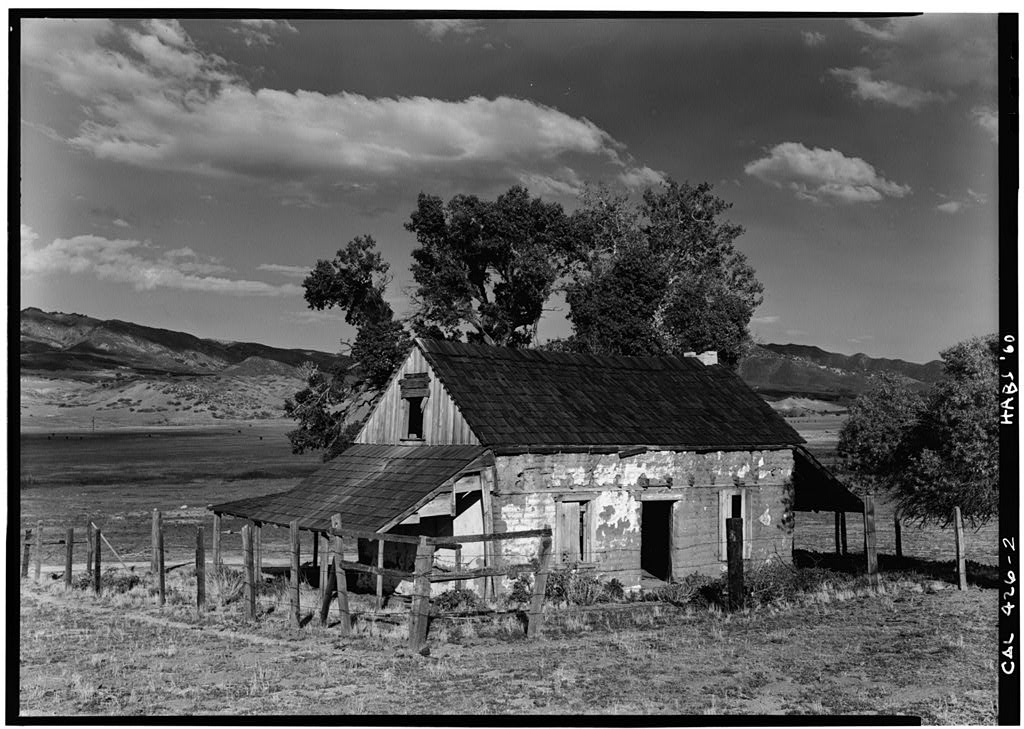

Crittenden Land & Cattle Company Purchased - September 1901

Vail, Gates, and Oscar Ashburn purchased the Crittenden Land and Cattle Company on September 7, 1901, from pioneer rancher Rollin R. Richardson. The Crittenden property encompassed 5,280 acres which included Richardson’s Pennsylvania Ranch in Monkey Springs Canyon.

This purchase provided additional rangeland close to the Empire Ranch and family access to a great swimming hole in Monkey Spring Canyon.

Ned Vail Visits Santa Rosa Island - September 1901

On September 25, 1901 Ned Wail wrote to his Aunt Agnes about a trip to Santa Rosa Island: “Walter and Mr. Vickers have bought the Santa Rosa Island and I made a trip there with them to see it. The party consisted of Mr. Vickers, his brother from New York, Tom Turner, a Mr. Willard from Tombstone, Walter & I and Banning. I was very much pleased with the Island and we had a pleasant party and a nice time. We rode over the Island a good deal, they have a lot of fine saddle horses on the Island and I think we rode over 20 miles a day where there. Most of the horses are large from 15 to 16 hands high and will weigh from 1,000 to 1,200 lbs. There are from 125 to 150 horses, mares, mules yet there. About 10,000 sheep and 300 or 400 cattle, the latter are very large short horn cattle and the fattest grass cattle I ever saw. The Island contains about 70,000 acres. I should think about 1/3 of it is rough and mountainous like Catalina and the balance is hilly with large mesas in the interior. The ground is very rich on most of the island and will oats, el filaria, cloves and other California grasses are abundant.

There are large barns, a large two story Ranch House, shearing sheds and dipping vats for sheep and cattle, a wharf and boat house with a life boat and a two story cottage furnished comfortably that made us think of Cousin Kate’s house in Plainfield. It even had a Bible and some old fashion books in it. There are beautiful views on the island and of the sea. Santa Cruz Island is only 6 or 8 miles East and looks close. Santa Rosa is a very windy place and so cool that we had to dress warm and a fire was comfortable at night (in August) but there is not much frost in Winter. Banning had a fine time hunting foxes and digging for Indian remains and relics and went home with a sack of bones, sculls and some stone implements which he divided with Professor Willard from Tombstone.”

In December Walter Vail shipped 4,000 head of Arizona cattle to Santa Rosa.

Harry L. Heffner - 1902

Around 1902 Harry Heffner became the manager of the Empire Ranch, a position he held until 1905. He first began to work at the Empire around 1893 and when the bookkeeper, Sinclair Oliver, died in 1895 he took over that position.

Heffner helped to organize the Arizona Cattlegrower’s Association in 1904 and held the office of secretary for the organization. Around 1905 he moved to California and continued his association with Vail & Gates.

Partial Interest in Warner Ranch Purchased - 1902

“Walter L Vail has purchased a quarter interest in the Warner ranch for $64,000. The ranch contains 11,000 acres. Title to the ranch recently was decided by the United States supreme court to rest In the heirs of the late Governor Downey.” [Los Angeles Evening Express 7/23/1902]

In 1903 Walter spent $10,000 to build a new house at Warner Ranch. “The house has all me modern improvements and then some, hot sulphur water being piped throughout the building.” [Los Angeles Times, 10/16/1903]

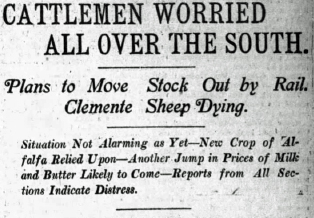

Drought Conditions - 1904

Walter Vail was interviewed for an article about the drought conditions “The loss of stock has as yet been small,” said Walter L. Vail of Vail & Gates. “The old feed on which stock is now grazing is in fairly good condition. Heavy rains might beat it down, wash out the nutriment and cause it to rot so as to destroy its value for stock. In that event there might be a few weeks before the fresh feed has grown in which stock would have pretty thin picking. As is usual at this time of year Southern California is now drawing from the regular supply in Arizona. Should there be no rain here, the effect on the beef supply would not be great until next summer or fall. On the Arizona range too principal precipitation of moisture is in the spring and summer, so there is no special concern regarding the weather conditions there now. “Of the beef consumed in Southern California, about 25 per cent is raised and fattened in Arizona and killed here. About 50 percent is bred in Arizona and shipped to Southern California as feeders. These feeders, when fattened here, are killed for local consumption. About 25 per cent of the beef consumed in Southern California is born, bred and fattened here. Both in consumption and output Southern California is not much affected by Northern California conditions. [Los Angeles Times, 1/27/1904]

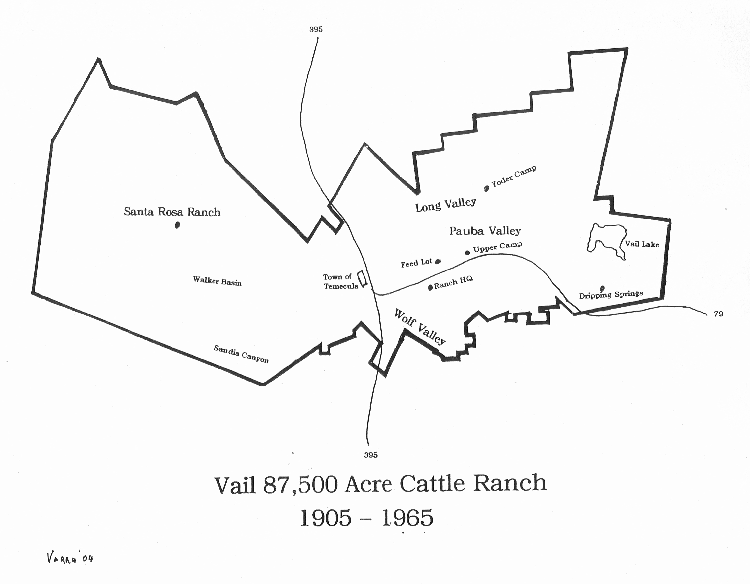

Purchase of Pauba & Temecula Ranches, 1905

“The great Pauba ranch, located in the southeast corner of Riverside county, has passed into the hands of a young Arizona cattleman, Harry L. Heffner, who will restock the ranch with thoroughbred cattle and horses.” [Los Angeles Herald, 7/15/1905] Though Heffner was the purchaser of record of the 39,000 acre ranch the funding was provided by Vail & Gates. “Immediately after the purchase… I[Harry Heffner] deeded the same, as a single man, to the Pauba Ranch Corp. in which I held a 1/8 undivided interest, for services herein mentioned.” [Harry Heffner].

Later that year Vail & Gates purchased the adjoining 2,200 acres Temecula Rancho and the townsite of Temecula.

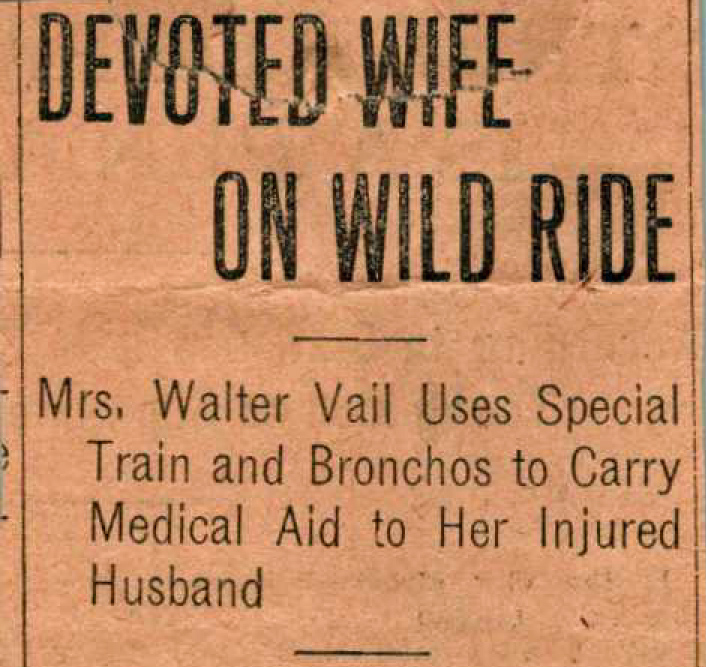

Walter’s Accident at Warner Ranch - October 1905

The round up season was in progress on the Warner ranch, San Diego county, in which Mr. Walter Vail is part owner. His presence was due to a desire to recuperate from an attack of illness. He entered Into the spirit of the occasion, and while in me Tuesday afternoon was riding rapidly, both cinches of his saddle either broke or slipped in such a manner that the saddle turned and Mr. Vail was thrown violently to the ground. He tried to save himself and his horse becoming frightened, he was dragged a considerable distance before he let go his hold on the horse. Walter G. Martin of Los Angeles, who is also a part owner of the ranch, happened to be nearby in a buggy and the injured man was brought to Warner Hot Springs, a distance of only four miles. It Is known that several of his ribs were fractured by the fall and it is believed he also sustained internal injuries. Upon arrival at the springs a telephone message was sent to Mrs. Vail at Los Angeles, and she replied that she would leave at once on a special train accompanied by the family physician. The train was run to Temecula and from there it was necessary for her to take a forty-mile drive.” [Arizona Daily Star, 10/6/1905]

Los Angeles Refugee Committee - April 1906

Citizens of Los Angeles mobilized after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake to aid those affected. Walter Vail was appointed as chair of the “Refugee Committee” and set about establishing camps for those displaced at various locations. The first camp was set up in Agricultural Park (now called Exposition Park), a 160-acre tract near Exposition Blvd. and Figueroa St.

The Agricultural Pavilion was equipped to house 500 women and children. Sufficient cots for 1,000 men were placed under the grandstand. Other camps were established at Fiesta and Ascot parks. By the end of April Walter had organized all the volunteers assisting refugees into departments and was managing the camps, food distribution, and dealing with concerns that the camps were attracting undesirables who were taking advantage of the city’s generosity.

Purchase of Santa Rosa Ranch - June 1906

In June 1906 Vail & Gates purchased the 47,000 acre Santa Rosa Ranch. Newspaper reports noted: “with headquarters in Los Angeles, had special reasons for desiring the ranch, for ho already owned the Pauba and Temecula ranches, covering about 38,000 acres, and joining the Santa Rosa property. The combined ranches now give him 85,000 acres of land.” [San Bernardino County Sun, 6/17/1906] The combined properties became known as the Pauba Ranch.

Walter Vail’s family guided this business enterprise effectively for over a half a century before the eventual dissolution of the holdings in 1964.

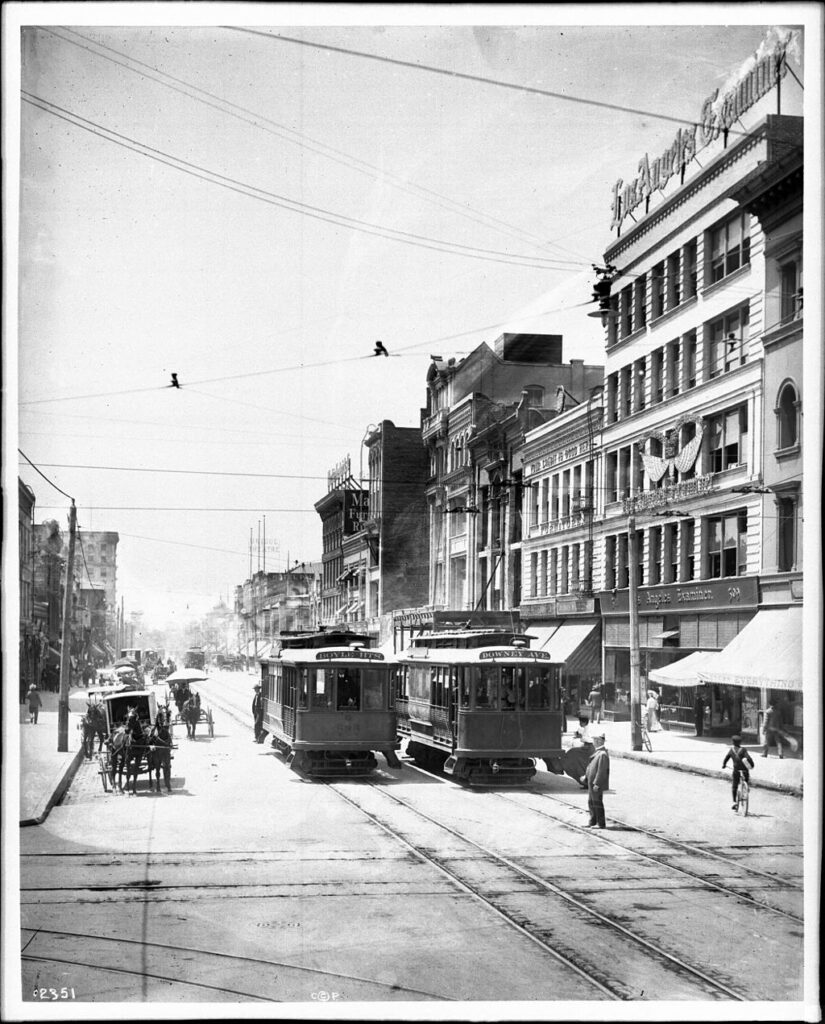

Walter Vail Dies - December 1906

Ironically, after surviving the Apache wars and the hardships of remote ranching life in Southern Arizona, Walter Vail’s life was cut short when he was killed by a streetcar in Los Angeles in 1906. He was injured on November 30th and died on December 2nd. He was 54 years old.

Walter did not have a will. His partner, Carroll Gates, took over as general manager of the Empire Land and Cattle Company, the Pauba Ranch Company, and other miscellaneous investments previously held in partnership with Vail, until its ownership under Walter’s estate could be settled. [Gregory Dowell, History of the Empire Ranch, 1978]

Margaret and the Children Regroup - 1907

“Dusty” Vail Ingram: “I remember Dad [William Banning Vail] telling me that after his father’s death, Nana Vail, she was wonderful. She evidently had a keen business sense, and she understood a lot of these things. And I think that, from what I gather from what Dad said, she sort of advised Walter. I mean, they discussed things. It wasn’t just that he did it, and that was it. Dad said that he can remember, after his father’s death, they had to do something, and so they formed this company, or developed it, so that Nana Vail had 50%, and then the other 50% was divided between the seven children. And he said he can remember that Russ [Nathan Russell Vail], who was the eldest, would be there stretched out on the floor hours and hours and hours into the night, working there on his stomach, as they were trying to figure out this, and figure out that, with what had to be done, and how they could manage, and so on. Because I guess Dad was still in high school at that time…” [Dusty Vail oral history 1993]

Settling the Estate - 1908-1909

To settle Walter’s estate a detailed inventory of all his property and other interests were conducted. Arizona territorial probate law required a ten-month timeline. On May 25, 1908, the court direct a final disbursement of the estate. Because Walter Vail left no will, one-half part passed to his wife, Margaret N. Vail, and one-fourteenth part each to his seven children: Nathan Russell, Mary E., Walter L., Jr., William Banning, Mahlon, Edward N., and Margaret R. Vail. [Gregory Dowell, History of the Empire Ranch, 1978]

By late 1909, in an amicable settlement, Gates deeded to the Vail heirs his interest in the Empire Land and Cattle Company, the Pauba Ranch Company, all land scrip in the name of Vail and Gates, his one-fourth part of the Crittenden Cattle Company, all interest in Warner’s Ranch, and half-ownership of a California land development company. In exchange, the Vails gave Gates their 4,034 shares of the Chiricahua Cattle Company stock, all interest in the Panhandle Pasture lands extensive real estate holdings in Kings, Kern, Fresno, and Los Angeles Counties, all 52,556 of the Vail shares in the Huntington Beach Company, and a cash settlement of $64,375. [Gregory Dowell, History of the Empire Ranch, 1978]